Favorite Baseball Rule Myths, Part 1

Baseball is riddled with rule myths, and if you search online you’ll find any number of websites that catalog lists of rule myths. At the UmpireBible we do the same, offering a list of Common Baseball Rule Myths. We list 42 baseball rule myths, describe the mythology, present the actual facts, and provide rule references throughout. But our treatments are brief. Here, I’d like to spend a bit more time, select a handful of my favorite rule myths, and dive a bit deeper into each of them.

1. The ball is dead on a foul tip

Before even beginning to discuss this myth, let’s back up a minute to be sure we understand the difference between a foul ball and a foul tip, because if you watch Big League baseball on TV (like I do) then you constantly hear commentators call any tipped foul ball that goes whizzing over the catcher’s shoulder a foul tip. That’s not a foul tip! It’s a foul ball.

The real issue, then, is not so much that a foul tip is a live (not dead!) ball, but instead making it abundantly clear that foul balls and foul tips are distinctly different things. We cover this topic in our article Foul Ball/Foul Tip, but let’s go over it briefly here.

Foul balls and foul tips are two distinctly different things. One results in a dead ball, the other is a live ball. One can result in strike three, the other cannot. One of them, by definition, must be caught; the other, again by definition, must not be caught. Foul balls and foul tips could not be more different.

Here’s the OBR definition of a foul tip: “A FOUL TIP is a batted ball that goes sharp and direct from the bat to the catcher and is legally caught. It is not a foul tip unless caught and any foul tip that is caught is a strike, and the ball is in play.”

In other words, a foul tip is a live ball. But let’s go a bit further and describe a foul tip explicitly:

- A foul tip is a pitched ball that skips off the bat and goes "sharp and direct" to the catcher "and is legally caught." That the ball is caught is the cornerstone of the definition of a foul tip. A ball that is not caught by the catcher is not (and can never be) a foul tip.

- A foul tip is always a strike; and, unlike a foul ball, a foul tip can result in strike three.

- A foul tip is a live ball. Runners can advance (steal) at their peril.

- If the catcher does not catch the ball, then it's a foul ball (dead ball). Period. That ball that is tipped by the batter and goes flying over the catcher’s shoulder to the backstop is a foul ball, not a foul tip. I can’t say that often enough. For clarity, let’s call that one a tipped foul ball.

- If a tipped batted ball hits the umpire first and then rebounds and is caught by the catcher, the is NOT a foul tip, nor is it a fly-ball out. The instant the ball touches the umpire in foul territory, it becomes a dead ball. (It's the same as a fly ball that hits a backstop or fence or anything else (except the catcher) in foul territory.)

- The mechanic for a foul tip is to brush the back of your left hand with your right hand, then give the strike signal. Some umpires swipe the back of their left hand two or three times, then give the strike signal.

2. A batter cannot be called for interference if he remains in the batter’s box

Perhaps no topic involving the rules of baseball gets more arguments, and is subject to more interpretation, that batter’s interference. You hear the arguments: The batter’s box is a safe haven. The batter’s box is not a safe haven. Just stay in the batter’s box and you’ll be okay. You must clear the batter’s box if the situation demands it. It’s a battle of opposites and the situation can be as fluid for umpires as it is for players and coaches.

Okay, let’s start with the rule book. OBR Rule 6.03(a)(3): The batter is out if “he interferes with the catcher’s fielding or throwing by stepping out of the batter's box or making any other movement that hinders the catcher's play at home base.”

As rulebook language goes, you can’t get much broader than “any other movement.” So batter’s beware.

Here’s the easy one: Batter swings at the same time a runner on first breaks for second. Maybe a hit-and-run is on. But it’s an outside pitch and the batter’s swing is off-balance and in the follow-through the batter falls across home plate (this is pretty common) just as the catcher comes up quickly for the throw down to second, and the catcher throwing collides with the batter falling across the plate. “TIME! That’s interference!” Batter’s out and the runner must return to his time-of-pitch base.

Here’s a hard one (one of many): Runner on second. Pitch in the dirt deflects off the catcher’s glove and shoots into the batter’s box, pings around the batter’s feet and the catcher goes for the ball but it squirts past the batter and the catcher is stuck trying to push through the batter’s legs trying to get the ball. The runner on second is sprinting for third by now and gets there safely while the catcher and the batter are tied up in the batter’s box.

Do you have interference on this one? Hard to say. Did the batter make “any other movement” that might have contributed to the catcher’s difficulty? Could the batter have gotten out of the way? Is the batter obligated to try to get out of the way? What if the batter tries to get out of the way and in so doing accidentally makes things worse for the catcher? Wouldn’t that be “any other movement”? Tough call.

This is why they call it a judgment call.

Another tough one is with a play at the plate, sometimes with a squeeze play for a runner on third (R3), or more typically with a passed ball or wild pitch with a runner on third. You have the catcher scrambling for the ball, the pitcher running in to cover the plate, and you have R3 barreling toward home. Get position and watch like a hawk.

On a play like this at the plate the batter is required to make an effort to get out off the way of the play at the plate. Problem is, a play like this happens very quickly and even you, the umpire, probably don’t realize what’s happening until a split second before the play blows up right in front of you.

One more thing about a play like this. When you call batter's interference on a play at the plate, who do you call out, the batter or the runner? The answer is, it depends. If there are fewer than two outs, you call the runner out. This, of course, prevents the offense from scoring a run on the play. With two outs, however, you call the batter out. Why is this? Because with two outs, if you call the runner out (to end the inning), then the batter is entitled to return as the first batter in the next inning – in effect, rewarding the batter for interference. In any event, no run scores.

We treat the topic of batter’s interference in greater detail in our article Batter’s Interference.

3. The player who bats out of order is called out on appeal

Not so. The one called out on appeal in the case of batting out of order is the player who failed to bat in their proper turn.

Okay, that’s the easy part. The hard part (and the part that’s created chaos more times than Methuselah could count) is how to go about fixing the base-running situation once batting out of order is discovered, appealed, and penalized.

Before digging in on this, let’s be sure we understand two terms: proper batter and improper batter.

- Proper batter: The correct batter at bat with respect to the official lineup. To belabor the obvious, there is always just one (and only one) proper batter at any given time.

- Improper batter: Any offensive player at bat other than the proper batter.

A batting-out-of-order appeal begins with the defense asking for time. The manager approaches the plate umpire and claims there is a batting-order infraction. At this point you consult the the official lineup (which is the one that you carry) to establish whether a player batted (or is batting) out of turn. This should be clear from the official lineup, as a batting order infraction will present itself in just one of three ways:

- An improper batter is currently at bat but has not yet completed his turn at bat.

- An improper batter has completed his turn at bat, but a pitch has not yet been delivered to a following batter.

- An improper batter has completed his turn at bat and one or more pitches have been thrown to the batter following the improper batter.

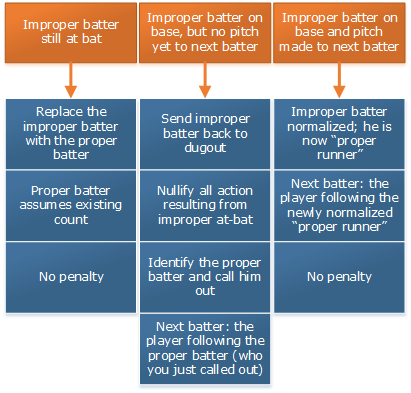

If upon consulting the official lineup you confirm that any one of these three cases applies, you have a batting-order infraction and you should uphold the appeal. You must then take one of three courses of action, depending on which of the three cases applies.

Case 1: The improper batter is still at bat. If you confirm that the plater currently at bat is an improper batter, you must do two things:

- First, send the improper batter (who is currently at bat) back to the dugout.

- Next, call the proper batter to the plate. The proper batter assumes the count (if any) that was on the improper batter. That's it. Play on. There is no penalty if the infraction is discovered while the improper batter is still at bat.

Case 2: The improper batter has reached base or otherwise completed his at-bat, but no pitch has been delivered to the batter following the improper batter.

If you confirm that an improper batter has completed his turn at-bat (and either reached base by any means, or has been put out) but there has not been a pitch delivered to the batter following the improper batter, then take the following steps:

- First, consult the lineup and identify the proper batter (the player who failed to bat in his turn in the lineup); call that player out.

- Next, nullify any action that resulted from the improper batter's at-bat. If the improper batter is on base, you must send him back to the dugout. If other runners advanced as a result of his at-bat, return those runners to the base they occupied when the improper batter advanced. If the improper batter was put out, the out is also nullified and comes off the board. (Note: If a runner advanced by stealing a base during the improper at-bat, that runner's steal stands.)

- Finally, call the next batter to the plate. The next batter is the player whose spot in the lineup follows that of the proper batter who failed to bat in turn, whom you've just called out. The batting order continues normally from there. If the batter who is now due up is already on base, then simply pass over him and move to the next player in the batting order.

Case 3: A pitch has been delivered to the batter following the improper batter.

If you confirm that an improper batter has just completed a turn at bat and the following batter, who is now at the plate, has received one or more pitches, the defense is out of luck. Once a pitch is delivered to the batter following an improper batter, then the improper batter (whether on base or in the dugout, if he's been put out) is now "normalized" and no further action is required. That batter is now (retrospectively) the proper batter. Importantly, the batting order then continues with the newly normalized batter and follows the official lineup from there.

Wrapping up

This all sounds somewhat confusing, but if you learn the rule and approach it systematically you can usually untangle it without too much trouble. The flow diagram here summarizes how to handle each of the batting-out-of-order scenarios.