Umpires in the Crosshairs

It’s difficult to recall a baseball season in which Major League umpires (and umpires in general) were subjected to the severity of criticism and the outright hostility that we see today. Clearly, the introduction of pitch tracking systems that show viewers pitch location in real time, letting us judge umpire performance pitch by pitch, contributes to the harsh trend. Increasingly, there’s a view that missing a pitch (even by inches) is a travesty that cheats the batter or the pitcher (depending on the miss) and is somehow undermining the quality of the game. We see a low-and-away pitch that’s maybe an inch off the black, which the umpire calls a strike, and sports bar erupts with beery hoots at the umpire.

It's said that the most difficult of all athletic feats to accomplish (across all sports) is getting a hit off a Major League pitcher. The best hitters in the world fail just shy of eight times out of ten and they're worth millions of dollars a year. One could also argue that a similar level of difficulty accompanies measuring by eye the trajectory of a baseball passing the vicinity of an invisible box (the strike zone) for merely hundredths of a second. But that’s just me.

We’re not talking about the occasional big miss. These happen to all umpires occasionally (but some umpires more than others), and in those cases outrage, if not justified, is acceptable, particularly if it’s a third-strike call. Rather, we’re talking about the dozens and dozens of pitches per game that clip the corners of the zone, in or out or up or down, just mere inches (or less) off the plate. It takes years of experience seeing literally hundreds of thousands of pitches to begin seeing these pitches correctly. Or nearly correctly. You should try it some time.

Hold on, though. I'm not here to make excuses, but to make a point. In an imperfect game fans expect nothing less than perfection from umpires. That’s unrealistic, but it’s an intractable truth. The overall problem is fueled in part by the performance of a small number of arguably weak umpires, Angel Hernandez, Laz Diaz, and C.B. Bucknor the most visible of the group. And there are others, but Angel Hernandez has become the lightening rod and he's been so roundly vilified, and for so long, that the ill will directed at him has spread like the flu across the entire umpiring landscape.

Trickle-down hostility

It’s not just MLB umpires who are experiencing this treatment. Hostility toward umpires has trickled down to amateur baseball across the board. Consider the rising number of incidents of hostility (and sometimes violence) toward umpires in amateur baseball. It seems that the outcry over umpire imperfections at the Major League level has given permission (in some mass hysteria manner) to baseball fans at all levels. And not just baseball. Similar trends have infected soccer, youth football, amateur basketball. It’s as though the “culture wars” have come to the playing field.

Not even Little League (Little League, fer cryin’ out loud!) is immune from hostility toward umpires. It doesn’t take but a few minutes browsing the Internet or rummaging around on YouTube to find examples of horrible behavior, even violence, toward sports officials, often by parents of players, and frequently directed at young officials. It’s truly appalling.

For several years I ran a youth umpire program as UIC of a Seattle-area Little League. While the behavior of adults, both coaches and parents, was almost always good, it normally took little more than a single conflict with an alpha-male coach or barrage of abuse from a single off-kilter parent shouting from the stands to push my 13- and 14-year-old umpires out of the game. It’s too much to expect a thirteen- or fourteen-year-old umpire to stand up to an adult, alpha-male coach shouting in their face. It’s not a level playing field and they couldn’t (or wouldn’t) put up with it.

Everywhere you turn you see hand-wringing accounts of umpire and referee shortages throughout youth sports leagues. And these accounts invariably cite the same problems with recruiting and retention: something along the lines of “It just ain’t worth it.”

This account I found on the CNN Business site is typical: America has an umpire shortage. Unruly parents aren’t helping. In the article you’ll see a video clip of a man attacking an umpire and knocking him unconscious. While extreme, it’s not atypical; the episode is indicative of how intense emotions can become in youth sports, and the increasingly volatile reactions on the part of coaches and parents. More typical are verbal assaults, and take it from me: the moms are every bit as emotionally “creative” as the dads.

So what about robot umpires?

There is a belief that at the Major League level there’s a solution to the consistency and accuracy problem (if, if fact, there is a problem) to be found in modern technology. Even a year ago I wouldn’t have said this, but now I believe MLB will be using “robot umpires” to call balls and strikes within the next couple of years. The technology is there and it’s been in use experimentally for some time in the minor leagues. In 2019, MLB implemented a radar-based automatic system for calling balls and strikes in the Atlantic League (an MLB-affiliated independent league), and in 2022 MLB expanded its automated strike zone experiment into AAA play.

In fact, all 30 Triple-A ballparks are fitted with automatic (robot ump) systems. While earlier experiments used a TrackMan radar system, the sport has now moved to a Hawk-Eye system (by Hawk-Eye Innovations), a 12-camera system that uses an optical array to track both the ball and player movements to an accuracy of about 2.5 mm (about a tenth of an inch). That’s pretty impressive from a technical point of view, and surely more accurate than the human eye.

MLB and the player’s union are still ironing out details, but it looks like momentum is moving toward a system that couples the Hawk-Eye system with player challenges (they’re calling it the ABS challenge system), in which players are allowed to challenge a set number of robot call per game. (Evidently, the robots also make mistakes.)

Inescapably, robot umpires will prove to be more accurate (and more consistent) than all of those fallible human umpires behind the plate, but to what advantage? Will more accuracy in calling balls and strikes lessen the vitriol and the hostility we see directed at umpires? Will the game improve? Will pitching improve? Will hitting? Just how will robot umpires change the game, and to what end?

Be careful what you wish for

Given the state of the technology, and given the fallibility of human perception, there’s no question that a high-tech, automated system would call balls and strikes more consistently than human umpires. But one must ask, is that necessarily a good thing?

There are a couple of reasons, and some possible unintended consequences, that should give us pause. Here’s one good example: the 12-6 breaking ball at the top and the bottom of the zone.

Having umpired for nearly two decades, I learned early that a curve ball breaking hard near the bottom of the zone, a ball that the catcher picks in the dirt just back of the plate, is never (never) a strike, even if the pitch is technically a strike. Any umpire habitually calling such a pitch a strike would be drummed out of the game. Even his umpire peers would upbraid him. But not the robot umps. They’d call it every time.

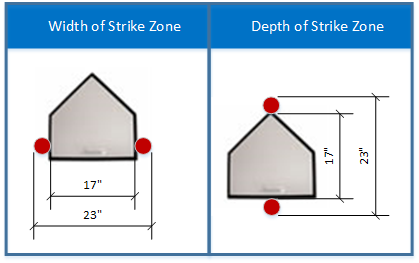

Let’s examine this. First off, the strike zone is a three-dimensional box that hovers over home plate. The plate is 17 inches wide and 17 inches deep. Second, the rulebook definition of the strike (Definitions: Strike (b)) stipulates that a called strike results “… if any part of the ball passes through any part of the strike zone.” In other words, if any part of the ball touches any part of the zone, it’s a strike. That’s the rule.

In reality, then, a breaking pitch that just clips the bottom front corner of the zone has effectively expanded the zone beyond its 17 inches by roughly the diameter of the baseball (the ball is about three inches in diameter). For the purpose of calling a strike, then, the “strike zone” is effectively 23 x 23 inches, not 17 x 17. Have a look:

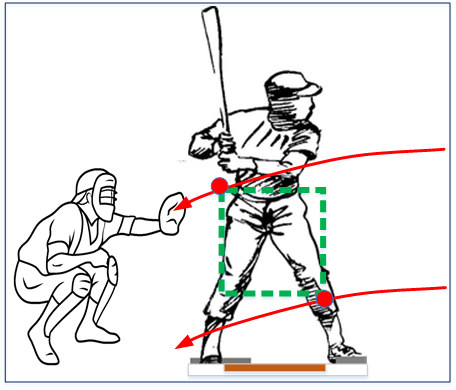

So here’s a look at two braking pitches that, while technically strikes because the edge of the ball touches the edge of the strike zone while passing over the plate, will never, ever, be called a strike in Major League baseball (nor in any amateur league north of 13 years old). One is the high breaking ball that catches the upper back edge of the zone, but which reaches the batter under the arm pits. The other is it’s evil twin, the low breaking ball, which touches the lower front edge of the zone, but which then dives into the dirt in front of the catcher. Lord help the umpire calling either of these pitches a strike.

When the robot umps start calling these pitches strikes, all hell’s going to break loose. And you’re going to see a similar violation of umpire (and batter) norms with sliders and other sweeping pitches that just clip the inside and outside corners of the zone.

When the robot umps start calling these pitches strikes, all hell’s going to break loose. And you’re going to see a similar violation of umpire (and batter) norms with sliders and other sweeping pitches that just clip the inside and outside corners of the zone.

Adam Kilgore in The Washington Post makes yet another argument against opting for the superior accuracy of robot umps. Kilgore argues that important elements of the pitcher-batter duel would be lost. The fine art of framing a pitch perfected by top-notch catchers would be lost, as would the art of expanding the zone by nibbling away at the outside corner, an art form perfected by the likes of Tom Glavine and others. Baseball is an imperfect game and meddling with the imperfections in a drive for perfection could have dire unintended effects.

If you take away these pitcher-catcher arts, Kilgore argues, “the preponderance of extreme velocity would only increase, along with all the problems it begets — more injured pitchers, more strikeouts, fewer balls in play, more pitching changes. If pitchers have to live in the zone, stuff rules.”

It seems to be a very American thing, this thirst for athletic gestures that feature power over finesse. We see this in professional golf as well, where the power drive now dominates the field of elite players (and where, incidentally, golf course design increasingly demands enormous drives off the tee to be competitive). This is vastly different from professional play on most European golf courses, which require control and finesse and only rarely rewards a 300-yard drive.

In baseball it’s the hundred-mile-per-hour fastball that’s become the darling of the game. Pitches in the professional game now have their speed posted in real time. Anything under 95 mph has become a snoozer. We count hits and runs, of course, but it’s the power game that fans find enchanting. Let’s hope this land of enchantment doesn’t end up diminishing the game. Or worse.

Postscript: Let's unpack what we see on TV

Like you, I watch Major League baseball on television and of course I note the pitch locations (we all do), evaluate that baseball-sized spot that pops onto the TV screen inside the rectangular box, the projection of the strike zone. This spot represents the pitch location, of course, or so they say. But is it really? Is this the location of the pitch when it touches the front of the zone? The middle of the zone? The back? Let’s remember, home plate is 17 inches wide and 17 inches deep, and the effective strike zone, as we’ve seen, is three-dimensional. It’s 23” wide and 23” deep and the ball's moving every which way.

Here's where I'm going with this:

If a pitch were to pass through the entire depth of the strike zone on a perfectly straight path (no break left or right, and no deflection down as gravity would have it), a trajectory that is absolutely dead straight, parallel to the ground for the entire 23 inches it transits the zone, then this spot that we see on our TV screens would be an accurate picture of the pitch location relative to the strike zone. And such a pitch could conceivably exist … in a vacuum — that is, if there were no gravity on earth, and no friction on the spin of the ball.

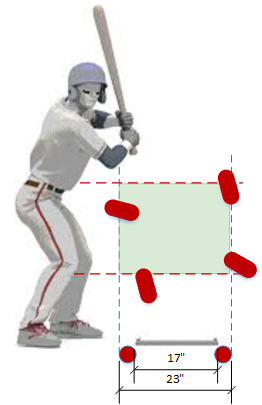

The fact is, there is no such thing as a pitch location that can be represented truthfully as a single baseball-size spot on the TV screen. Such a pitch location does not exist in the real world. In all cases, a pitch has lateral movement, or vertical movement, or more often both, as it passes through those twenty-three inches of the strike zone.

Therefore, any representation of a pitch’s location transiting the entire strike zone could only be accurate if it takes the shape of the baseball elongated to depict its position as it breaks through its entire transit though the zone. To be accurate, then, the image superimposed on our TV screens should be elongated and look something like the examples in this image:

And what now do we think about that pitch we see on the TV screen just inches off the plate that the umpire allegedly screwed up by calling a strike? Maybe. But maybe not.