Mechanics

Covering Rundowns

Covering Rundowns

While covering rundowns is pretty straightforward, there are a handful of important nuances:

- Angle over distance is paramount. As you change directions and move back and forth with the runner, don’t forget to preserve angles in case the play gets to the base. In other words, don’t get sucked too deeply into the rundown. Keep your distance and preserve your options.

- Keeping your distance from the rundown also decreases the amount of running you need to do to stay with the play.

- With two umpires on a rundown, normally it’s the umpire whom the runner is approaching who makes the call.

- In cases where a partner joins a rundown in progress, the originating umpire stays with both sides until the partner signals verbally (and loudly) “I’ve got this end.” However, for the umpire joining the rundown, only call “I’ve got this end” when the runner is moving away from you so you’ll have the runner when he changes direction heading back to you.

- When in the first to third situation (runners on 1B and 3B), umpires must handle the rundown by themselves:

- On a rundown between third and home (and a runner on first base), the PU has it all because U1 must stay in the working area to cover in case R1 tries to advance to second.

- On a rundown between first and second (and a runner on third base), U1 has it all, because the PU must stay home to cover in case R3 tries to advance to home.

- Obstruction. You must remain alert to obstruction, particulalry if the rundown becomes extended with many throws and changes of direction. The fielder, once he throws the ball (and is no longer in possession of the ball), must not in any way impede the progress of the runner. If he does by colliding or otherwise impeding the runner's progress, you have obstruction. The award in this situation is the base beyond the last base legally held.

- Details

- Hits: 25372

Working Area & The Library

Working Area & The Library

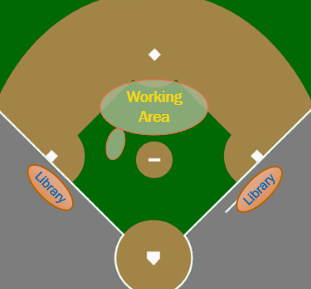

In addition to knowing the start positions and basic rotations, the base umpire (U1) must also be familiar with the working area and the library. While the library comes into play primarily with larger crews employing three- and four-man mechanics, the working area is important with all crew configurations.

Working Area

The working area is your friend. When your start position is B or C, most of your responsibilities are going to take place in the working area.

The illustration depicts the working area on the infield, behind the pitcher's mound, and ranging to left and right. However, the boundaries in the oval shown here are not etched in stone. From a position between the mound and second base, and extending toward the first and third base lines, you slide left and right to get the proper angle on the plays that you're responsible for.

That little tail on the working area that you see between the mound and third base is an extension that you move into when you have a play at third. Notice that when you move from the working area into the tail, you don't want to move parallel to the baseline. Rather, move toward a point midway between third and home. This gives you a far better angle on a play at third.

Areas of responsibility for the field umpire that normally take place in the working area include these:

- All plays at all bases, except ... On a two-man crew, you have all plays at all bases, except when you are in a first-to-third situation. We talk about that exception elsewhere. With multiple runners, though, you need a head on a swivel, as they say, and you need to stay with the ball.

- Plays at third base. Plays at third will draw you out of the working area to the tail we talked about. Notice (and this is important) that U1 does not move in a line parallel to the base path when getting set for a play at third. Instead, he moves in the direction of the home team dugout so that he gets a good angle on the play at third. However (this is important): don't go deep into a play at third if there are other runners advancing. You may need to be able to quickly pivot and pick up a play at second.

- Base touches and tag-ups. You have responsibility for tag-ups and base touches on all runners at all bases. This changes when there are multiple runners; in that case the plate umpire has touches and tags at third base.

- Catch/no-catch in the cone. You should drift in the working area to best position yourself for the catch/no-catch call and (to the best of your ability) to also line yourself up to see the runner on second (R2) tag up.

- Catch/no-catch of pop-ups to the infield. The PU has most catch/no-catch calls on fly balls to the infield, but pop-ups that bring the fielder right to your position belong to you. We talk about this in more detail in the article Catch/No-Catch Coverage.

Don't get sucked into a play at a base. What does this mean? It means that with multiple runners and the potential for multiple plays in quick succession, you don't want to get sucked too far into any one of these plays. Sacrifice distance to maintain your angles. For example, if there is a play at third, and you hustle to get close for the play, and then there is a quick throw to get a runner advancing to second, you're going to have a terrible angle on (and may end up screwing up) the play at second. Stay in the working area when there are multiple runners and position yourself to get good angles rather then close distance.

The Library

The library does not come into play in two-man mechancics, but it is such an integral part of three- and four-man mechanics that it's important that you're familiar with it. And where did "the library" get it's name? It's called the library because it's an intermediate position where an umpire pauses to literally read the action and prepare to then rotate as action on the field dictates.

In three- and four-man rotations, on balls hit to the outfield, the umpires in A and D positions frequently complete an initial assignment (for example, U1 gets the batter-runner's base touch at first), then releases the runner and drops into the library to read the action, and then, if necessary, rotates down to home plate (that is, when the PU has rotated up to third).

This is just one hypothetical scenario of a great many that employ make use of the library.

- Details

- Hits: 28890

Catch/No-Catch & Going Out

Catch/No-Catch & Going Out

I've reviewed dozens and dozens of umpire mechanics manuals, PowerPoint presentations, PDFs and whatnot, and I've seen enough diagrams of umpire movements and rotations to literally numb the mind. I'm not saying these are misguided efforts; rather, they often tend to take something rather simple and make it way more complicated than it needs to be.

As we did with the Basic Rotations, we're going to simplify. As you gain experience, you can build on these basic principles. But the basics themselves get you 90% of the way to proficiency. And we're going to apply these principles to two issue: who covers catch/no-catch under a given set of circumstances, and when should the field umpire (U1) decide to go out to cover a catch in the outfield. What follows applies to umpires in the two-umpire system.

Catch/no-catch coverage depends on the field umpire's start position. When U1 starts in the A position (that is, when there are no runners on base), there is one set of assignments. However, when U1 is in the B or C positions (with runners on), the situation changes.

Let's start with U1 in A

With U1 in A, on a batted ball to the infield, U1's responsibility is covering the batter-runner to first base and beyond. On a batted ball to the outfield, however, U1 must decide immediately whether to go out on the catch/no-catch, or instead come inside and take the runner.

If U1 decides to go out to cover the catch/no-catch, then the plate umpire takes the batter-runner all the way. If, on the other hand, U1 decides not to go out, but instead to come inside, pivot, and stay with the batter-runner, then the plate umpire has catch/no-catch, as well as fair/foul if the fly ball is near the foul line.

The decision to go out or come inside rests entirely with U1. The plate umpire must read U1's intentions and respond accordingly. That said, there are some guidelines on deciding when to go out and when come inside. The guidelines rest primarily on two issues: (1) the batted ball's location in the outfield, and (2) the nature of the batted ball.

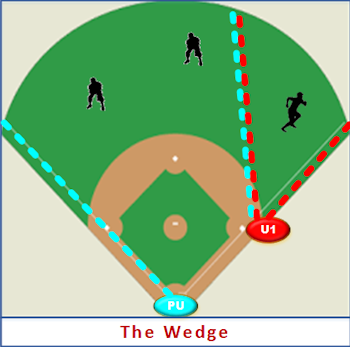

With respect to U1 going out, there is a huge disconnect between what is written and what actually happens. In most umpire manuals (a good example is the Collegiate Commissioner's Association (CCA) Manual), the "book" has U1 covering all of the outfield from center fielder to the right field line. But you won't see this in practice. In practice, U1 goes out in a much narrower wedge. So that's what I'll call it: the wedge.

With respect to U1 going out, there is a huge disconnect between what is written and what actually happens. In most umpire manuals (a good example is the Collegiate Commissioner's Association (CCA) Manual), the "book" has U1 covering all of the outfield from center fielder to the right field line. But you won't see this in practice. In practice, U1 goes out in a much narrower wedge. So that's what I'll call it: the wedge.

In reality, U1 goes out from the A position far more conservatively than most umpire manuals would have you believe, and the plate umpire (PU) covers far more ground on catch/no-catch coverage.

Here are guidelines to help inform U1's decision to go out:

- If the ball is over U1's head and entails a potential fair/fould call, and the right fielder is racing in the direction of the foul line, then U1 must turn, position himself on the foul line, perhaps take a few steps out, but then get set for the call.

- On a deep fly ("trouble") ball that has the right fielder funning for the fence (or conceivably, the center fielder running hard into the wedge), you should go out for the potential home run call.

- If you see two fielders converging on the same fly ball in the wedge, you should go out for the potential error.

- On a line drive to the outfield that a fielder is running in to field, and which could be a catch below the waist, or even a shoestring catch (or trapped ball), you should go out to get this trouble ball.

Important: When going out on a trouble ball, do not run straight at the fielder attempting the catch. Instead, take a line about 20-30 degrees off the straight line so you get an angle on the catch. This is particularly important when you have a shoestring catch/trapped ball decision to make.

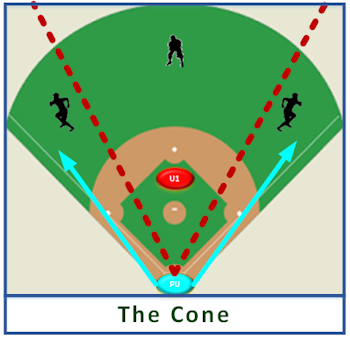

With runners on base

With runners on base, U1 is in either B or C, depending on the base-runner configuration. Regardless of which side of the mound U1 is on, the catch/no-catch mechanics are the same. That is, now U1 owns the catch/no-catch call over the majority of the outfield – over the entirety of the cone. The PU, then, has catch/no-catch in cases where the left or right fielders are moving toward the foul lines to make the catch.

The cone is that portion of the outfield roughly defined by the left and right fielders moving straight back, straight forward, or moving in toward center field. In simpler terms, if a fly ball is not pulling F7 or F9 toward a foul line, then that fly ball is in the cone and the catch/no-catch call belongs to U1. If the fly ball is pulling F7 or F9 (or, in some cases, F3 or F4) toward a foul line, the fly ball is "on the line" and the catch/no-catch belongs to the PU.

The cone is that portion of the outfield roughly defined by the left and right fielders moving straight back, straight forward, or moving in toward center field. In simpler terms, if a fly ball is not pulling F7 or F9 toward a foul line, then that fly ball is in the cone and the catch/no-catch call belongs to U1. If the fly ball is pulling F7 or F9 (or, in some cases, F3 or F4) toward a foul line, the fly ball is "on the line" and the catch/no-catch belongs to the PU.

It is the responsibility of the PU to call U1 off if he's taking ownership of a fly ball that is on the line. The plate umpire must call loudly (so his partner can hear) "I've got the ball!" (or the 3rd base side), or "I've got the line!" (on the 1st base side).

Important: We're learned elsewhere that, with runners on base, the PU is responsible for base touches and tag ups at third base. However, when the PU takes catch/no-catch on the first base line (and calls I've got the line!), he is no longer in position to see touches and tags at third base, so in this situation he is relieved of that responsibility. U1 must recognize this switch and take over touches and tags at third.

Do we ever go out with runners on?

One the big diamond, the B and C positions are inside the basepath. (See start positions if you need a refresher.) There is an axiom that says you never ever go out from inside the basepath. That is, you never cross the basepath (risking a collision with a base runner) from a position inside.

Here we get to another set of instructions where there is a disconnect between what is written and what actually happens on the field. There are some mechanics manuals (NCAA is one of them) where, in a three-umpire crew, the umpire in B or C is directed to go out to the outfield to cover catch/no-catch from his start position inside the basepath. In that case, the third umpire comes inside from the D position, and then U3 and PU revert to the two-umpire system.

However, I have seen a lot of NCAA baseball games (Divisions I, II, and III) and I have never (not once) seen an umpire cross the basepath to cover catch/no-catch in the outfield. I'm not saying it doesn't happen; I'm just saying I've never seen it.

With regard to the two-umpire system, then, I'm comfortable with the direction to never, ever go out from inside with runner on base. There are two reasons for this – one of them a good reason, the second a really good reason.

First off, there's the issue of a potential collision with a base runner. Why risk it? And the second, even better reason, is that if U1 goes out, then the PU is left alone with the entire infield and all base runners. And that's asking for trouble.

So don't go out from inside. Just don't do it. Rely instead on the cone-and-lines division of responsibilities and let it go at that.

On the Small Diamond

When working the small diamond (60-foot base paths), the coverage changes somewhat.

- Details

- Hits: 43824

Working the Plate

Working the Plate

As we've said already, working the plate is, in many respects, the cornerstone of the umpiring avocation. It's the image that comes to peoples' minds when they think of the baseball umpire. Of course, we know that umpiring is a team sport, and that everyone on the crew plays an indespensible role (and that a mistake from one is a mistake for all); but, that said, the plate umpire is, by rule, the umpire-in-chief and manager of the game.

Important: You should read this article together with its companion article, Calling Balls & Strikes. The two should be read together.

We have a problem, though. More than any other subject covered by UmpireBible, you can't teach anyone how to work the plate from the written word. It's like teaching golf out of a book. A book can help with the rules, and it can describe correct technique, but never in a thousand years will anyone learn to hit the ball by reading about it. A person has to go out and do it, and practice and practice, and they'll also need an observer and teacher. And over time, with repetition, they learn.

Which isn't to say this is a waste of time – talking about working the plate here in this article. The fact is, you can pick up some important information. And that's what we're going to focus on. The information. But to really learn how to work the plate, you're going to have to go out and just do it.

A great deal has been written over the years about working the plate, so I won't try to reinvent the wheel. Instead, let's start with two distinguished umpire-writers, Peter Osborne and Carl Childress. For over two decades a series of articles by these writers have played a role in the teaching umpires their craft. On many points, however, Osborne and Childress disagree. And that's the beauty of pairing them.

I encourage you to read for yourself Peter Osborne's three-part series, as well as Carl Childress's thoughtful two-part response. I draw largely on their insights and expertise in what follows.

By Peter Osborne:

Part 1: Working the Plate: The Basics

Part 2: Advanced Ball and Strike Calling

Part 3: Myths that Get in the Way of Calling Pitches

By Carl Childress:

Working the Plate: Another View, Part 1

Working the Plate: Another View, Part 2

Two important points about the Osborne and Childress articles: First off, they disagree on many points. Second, some of their guidance does not agree with current accepted practice. I see both points as advantages, not weaknesses.

We're going to cover three topics:

The Setup

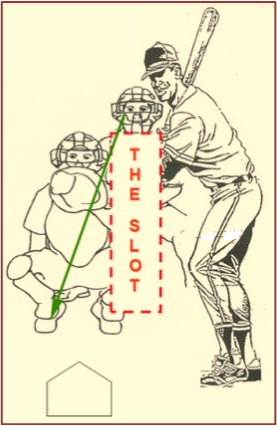

One of the biggest disagreements between Osborne and Childress is about the initial setup – the box vs. the slot. (The other setups that are mentioned, the scissors and the kneeling position, are outdated and seldom used; they are not recommended and I won't waste any time on them. For the record, current teaching focuses almost entirely on the slot.)

The Box

In the box position, the umpire lines up directly behind the catcher, about 12 inches behind, and positions his head so that his chin is no lower than the top of the catcher's head. Your feet are parallel, about shoulder width.

At one point, Osborne says about the slot position, "All good umpires in the U.S. work what is called the slot. If you do not work the slot, you will be perceived as inferior, regardless of what your actual results are."

This opinion is generally accepted as true, including by me. The box position is rarely used and is fading away. The slot is what you should focus on and learn. It's what almost all (in fact, probably all) umpire training schools and teacher instruct. If you decide to adopt the box, you'll be largely on your own.

Childress fleshes out the main deficiencies of the box: "The practical objection is that since few umpires use that stance, it's difficult to find good trainers. The philosophical objection is that the umpire is farther removed from the low pitch." This latter point frames the central problem with the box. While you have a good view of the edges of the plate, inside and outside, you have a terrible view of the low pitch. Given the extent to which modern pitching "lives low," this is a considerable problem. The modern strike zone is lower (by rule) than in bygone days, and with it the box setup has become obsolete.

The Slot

There is no perfect position for the plate umpire. Every position has certain deficiencies. We'll talk about the deficiencies of the slot position in a minute, but first let's learn it.

Important: As with many aspect of working the plate (and as we've said before) you're not going to learn proper setup in the slot position from a book (or web page). You need hands-on instruction. You need to be observed by a knowledgable teacher who can correct your posture and positioning. You need to attend training sessions or clinics.

The literal "slot" is that open space between the batter and the catcher. You want your head in the slot so you can see the pitch all the way from the pitcher's release point to the catcher's glove, and you want to be able to see all of the plate.

In the slot position, then, the plate umpire places himself squarely in that opening. The head is positioned on the inside portion of the plate and the umpire's head is above the catcher's. The view of the plate is from the inside-top.

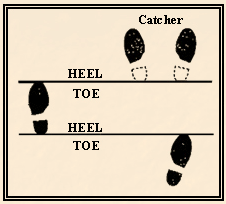

Let's look more closely, though, starting with the feet. You set up in the slot by stepping into position with your feet configured in the heel-toe.

Look at the image on the left, which depicts the heel-toe setup for a right-handed batter (left-handed batter is mirror image). The left foot sets up in a position with its toe on a line created by the back of the catcher's feet. The right foot, then, lines its toe up on a line created by the back of the left foot. (Expressing it in words makes it sound confusing. Just look at the image.)

Look at the image on the left, which depicts the heel-toe setup for a right-handed batter (left-handed batter is mirror image). The left foot sets up in a position with its toe on a line created by the back of the catcher's feet. The right foot, then, lines its toe up on a line created by the back of the left foot. (Expressing it in words makes it sound confusing. Just look at the image.)

Note: This depiction of foot positions is for general guidance only. The umpire's height and other factors will affect how wide your feet are placed. The important part of the setup is positioning yourself so that your head is in the slot, and that you have full view of the plate.

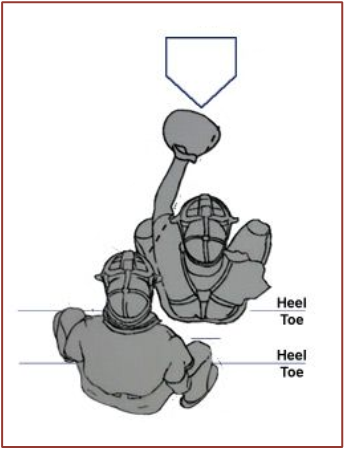

This positioning gives you a nice stable base and allows you to drop into your stance quite easily by simply "sitting" into it. It also allows you to lower or raise your head height be simply spreading or narrowing your stance. The image on the right shows you the setup in a top-down view.

This positioning gives you a nice stable base and allows you to drop into your stance quite easily by simply "sitting" into it. It also allows you to lower or raise your head height be simply spreading or narrowing your stance. The image on the right shows you the setup in a top-down view.

Osborne finishes off the setup this way: "Your nose ends up being lined up with the inside corner of the plate or slightly to its left [depending, in part, on how the catcher sets up], but never over the plate. Your body, because of the heel-toe alignment, is facing the second baseman, and pro school teaches that the head should be square to the pitcher. You are now in a position to accept the pitch. As the pitcher winds up you snap down so that the bottom of your chin is no lower than the top of the catcher's helmet."

Tracking the Ball & Seeing the Pitch

Can we all agree on one thing? That it's important for the plate umpire to see the pitch?

The number one requirement

The number one requirement for seeing the pitch is keeping your head still and tracking the ball with your eyes. I put all of that in boldface because it is so important. In fact, this is so important that I'm going to say it again: The number one requirement for seeing the pitch is keeping your head still and tracking the ball with your eyes.

This does not come naturally. You must train yourself to keep your head still and track the ball with your eyes, not your head. Our natural tendency is to turn our head as the ball approaches the catcher's glove. In fact, one of the biggest tip-offs that an umpire is not well trained is his tendency to move his head and sometimes even his body. On outside pitches, this movement is particularly noticeable.

Which brings us to the outside pitch

Both Osborne and Childress note that the weak spot (the main deficiency) of the slot position is difficulty calling the low-and-away pitch. In the slot position, your eye is at or near the top-inside corner of the strike zone. This makes low and away the farthest point from the eye.

I would even go a bit further and say that both of the outside corner pitches (high and low) are the most challenging pitches to call. Pitches up-and-away are the farthest from your primary reference points (plate, batter, catcher). More than any other pitch, up-and-away requires that you know it every bit as much as you see it. And that just takes practice.

Pitches inside, and the high stuff

Calling the inside pitch is relatively easy. Inside pitches are right in your face so they're pretty easy to call – so long as your timing is good (that is, you're not rushing it). Also, you're positioned such that a pitch off the plate inside is pretty easy to see as a ball. Your main concern on the inside pitch is high/low. But again, if your eye is at the top of the zone, the high strike inside is pretty much right in your face. The low one is just inches from the batter's knees, so your reference point is adjacent to the pitch.

The common mistake on the high pitch is calling a bad strike on a pitch just above the zone. Of course, when adjusting for age and level, it's the top of the zone that varies the most, so it's sometimes difficult to dial in the top of the zone if you move frequently from one age group to another. Most of us do. We talk more about this in Calling Balls & Strikes.

Breaking balls

Calling breaking pitches are most challenging of all, particularly if your timing is too quick. On breaking pitches you have to be very attentive. A high breaking ball could "stick" the catcher's glove right at his chest, but still have come over the top of the zone. Same with cutters and sliders that move in and out. A ball can break sideway into or out of the zone at the last moment. You must be diligent on these. Most important is seeing the pitch all the way to the catcher's glove, resisting the temptation to call the pitch too quickly.

Of course, you tend to see pitches like these at higher levels – generally 14 and older – which is a level that, if you're a new umpire, you shouldn't be working yet. Instead, you can cut your teeth on the younger kids who pitch lollipop floaters that aren't really breaking balls, and yet cross the plate in much the same way. Rather than breaking, they're arcing across the plate, and these require the same attention as true breaking balls. These, again, you learn to see. And also demand good timing.

The number one mistake

The number one mistake you see with inexperienced umpires is their not seeing the ball all of the way to the catcher's glove. They see it most of the way, make their decision (ball or strike), and then the ball breaks or drops and you end up with a ball called strike or strike called a ball.

This happens unconsciously, of course. But it's still a perfect segway into the issue of timing, which is cause of this problem – poor timing, that is. A breaking pitch over the middle of the plate, but low (even in the dirt) looks absolutely perfect when it's fifteen feet from the plate. And that's where many inexperienced umpires are making their ball/strike decision – probably only a dozen thousandths of a second before the pitch reaches the catcher's glove. But if you're calling a pitch the instant it hits the catcher's glove, you're almost certainly making your decision while the ball is still in flight. And that's why those decisions are so often wrong.

Timing Timing Timing

If there's one area where Osborne and Childress agree wholeheartedly, it's on the matter of timing. Osborne puts it well:

The first step in developing good timing is to see the pitch all of the way to the catcher's glove. You think you see it all the way, but you probably don't. You must train yourself to not just see the ball all the way to the catcher's mitt, but to then notice the position of the mitt. If you permit yourself to notice the position of the mitt after the catch, then you've seen the ball all the way.

The most uniformly prevalent bad habit we see in new umpires is the impulse to call balls and strikes quickly. The instant the ball hits the catcher's glove (and sometimes even before it hits the glove – believe it or not) you hear it: "steee-Rike!" It's painful to watch because, as an experienced observer, you know that when the call is made simultaneously with the catch that the decision was made while the pitch was still in flight. We all did this when we first started out, but then we learned about proper timing.

The second and equally important step is to pause once the ball hits the mitt. This is a hard habit to develop because it doesn't feel natural. But it's critically important. You have to practice it.

Here's the drill. Once the ball pops the mitt, pause for a full second. During this pause, allow yourself to quickly replay the pitch, make your strike/ball decision, the vocalize your call silently to yourself, and only then do you verbalize "ball" or "strike." Let me reiterate:

- Once you've seen the ball hit the glove, replay the pitch in your mind.

- Make your decision – ball or strike.

- Vocalize your decision silently to yourself.

- Finally, verbalize your call – either come up with your strike call, or stay down and verbalize "ball."

This is going to feel awkward at first. It will seem like you're silent for a long time, for too long. But it's not a long time. It only feels that way.

What are the advantages of methodical timing? The advantages are several:

- First, and perhaps most importantly, concentrating on your timing prevents you from calling your pitches too quickly. That is your biggest enemy – the impulse to call your pitches rapidly.

- Good timing minimizes the tendency to make mistakes on close pitches, which helps ensure consistency. Consistency lives and dies on the corners. And few things get you in more hot water with coaches and pitchers than inconsistency with your strike zone. Coaches are not stupid. They can see when you're being inconsistent and they will call you out on this. That will unnerve you and make things even worse.

- Difficult corner pitches sometimes makes you stop and think. If you call your pitches quickly, but then come to a tough pitch and hesitate a moment while you think, this infrequent pause is nothing short of you shouting at the top of your lungs, "I'm not really sure about this one!." Believe me, everyone over nine years old will understand this. If, on the other hand, you give yourself time on every pitch, then only you (and maybe your catcher) will know the really tough ones.

Accuracy, consistency, fewer arguments, greater confidence – what's not to like about good timing. But, like everything else in umpiring mechanics, it takes practice. You have to train yourself (with some help from a good instructor) to find your timing, and to then ingrain it so that it becomes perfectly natural and remains consistent.

- Details

- Hits: 79629