Mechanics

Calling Balls & Strikes

Calling Balls & Strikes

Calling balls and strikes goes to the very soul of umpiring baseball, and I devote a lot of space to the subject, both here on the UmpireBible, as well as on the UmpireBible Blog (see, for example, Calling Balls & Strikes: The Matthew Effect).

We're going to cover two topics in this article:

Important: You should read this article together with its companion article, Working the Plate. In that article we cover topics like proper setup, timing, and mechanics.

The Strike Zone

The strike zone is defined in the rule book Definitions (strike zone) as a three-dimensional area over home plate that extends from the hollow at the bottom of the knee to a point "at the midpoint between the top of the shoulders and the top of the uniform pants." The top of the zone is going to take some discussion, so let's save that for later. Let's start with the "over home plate" part.

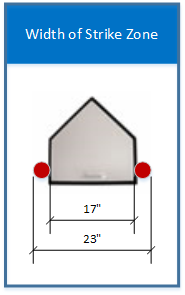

How wide is the strike zone?

Home plate is 17 inches wide (Rule 2.02). A baseball is a shade under three inches in diameter (2.94436644720 inches, to be exact, but let's just call it three) (Rule 3.01). Because the definition of a strike specifies that "any part of the ball passes through [touches] any part of the strike zone" (Definitions (strike zone)), we can conclude that the strike zone is 23 inches wide. Note that the black on the edge of the plate is not part of the plate.

How tall is the strike zone?

The height of the strike zone is trickier because it's based on the physical attributes of the batter, so the dimensions vary. Not only that, but (let's be honest) the dimension of the upper limits of the strike zone vary somewhat depending on what level of baseball you're doing. If you're doing upper level youth ball (players over 14) or men's leagues, you're calling a clean zone where the top is about a ball above the belt.

But if you call that zone for ten-year-olds, you're going to be walking batter after batter. At the lowest levels of kid-pitch baseball, you're calling pretty much shin to shoulder. And you're probably also giving a ball on the outside of the plate, maybe a ball-and-a-half (but not the inside, because you don't want hit batters).

But if you call that zone for ten-year-olds, you're going to be walking batter after batter. At the lowest levels of kid-pitch baseball, you're calling pretty much shin to shoulder. And you're probably also giving a ball on the outside of the plate, maybe a ball-and-a-half (but not the inside, because you don't want hit batters).

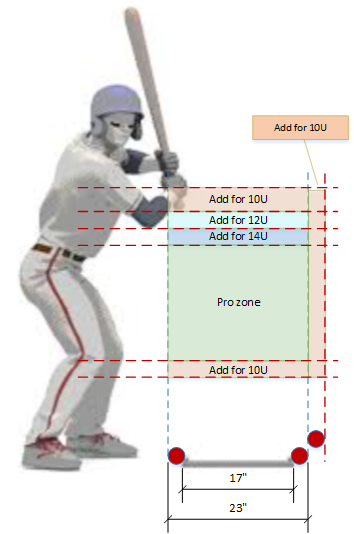

On the left is an abstracted view of a batter with the strike zone drawn in. The point is to give you a conceptual view of how to adjust for age and level. These lines are not written in stone, so think of this as a generalized guideline on how to make adjustments for player age and ability.

Here are some important take-always from the illustration:

- What I call the "Pro zone" is pretty much the strike zone in professional, college, high school, and higher levels of club and travel ball – pretty much 15 years old and up. The top of the zone is somewhat lower than what's specified in the rule book. I can't explain this except to say that the tradition and culture of baseball has modified the written rule with a generally accepted "real-world" interpretation of what the strike zone should be. In the real world, the top of the zone is about a ball above the belt.

- Note that the strike zone expands upward to adjust for age and ability, not outward or downward – that is, until you reach the really young kids, roughly ten and under. However, these ages are not written in stone. You must adapt to the skill level, which tends to correlate with age, but doesn't always.

- Where necessary, you can expand the zone outward off the plate. Only you, the pitcher and the catcher can see this, so as long as you're consistent you won't get complaints. You can take it a ball to a ball-and-a-half off the plate. But again, don't give away inside because that will lead to hit batters.

- The adjustment I've indicated for players aged 14 and under sets the upper limit of the strike zone at roughly where the rule book specifies ("the midpoint between the top of the shoulders and the top of the uniform pants"). This upper limit typically corresponds with the bottom of the uniform letters, but this can vary.

- For players aged twelve and under, bring the level up under the armpits, but keep it below the hands. By this age coaches are teaching their players to never touch a pitch above the hands. Try to work with this. The illustration doesn't show it, but at this level you can easily give a ball on the outside.

- For the really young players you have to give quite a bit. They're just recently out of t-ball and coach-pitch leagues and it's all they can do, sometimes, to reach the plate, let alone hit the strike zone. Add to this a quite natural fear of the ball that many young batters have and you have a recipe for a walk-a-thon. You must keep the kids at the plate swinging the bat and to do this you pretty much adopt the position that any pitch that's hittable is a strike. Give a ball on the outside, give a ball below the knees, and bring the top of the zone up to the shoulders. Believe me, the coaches will appreciate this. (Note: This prescription changes when you reach All-Star tournaments. By the time you have the best players, even ten-year-olds do surprisingly well, so at tournament time you're going to be closer to the 12U zone.)

- Don't give away inside the strike zone. You can give away outside, when needed, but don't give away strikes on the inside. If you do, you're going to start getting batters hit by the pitch.

- You must be consistent. I can't emphasize this enough. And sometimes this is hard to do. For example, you may have weak pitching on one team and quality pitching on the other. The temptation is to give the weak pitcher some help so you don't spend the entire day walking batters, but you must resist this temptation. If you give one pitcher some help on the outside, for example, then you must give the same leeway to the other pitcher.

- Don't forget that the strike zone is three-dimensional. We're going to talk about this in the sections below. But for the record, the strike zone is 17 inches deep. This is why breaking balls are challenging to call. This is even moreso for the lollipop floaters you get from the young kids.

Balls & Strikes

Okay, here's where the rubber meets the road. But before we start, let me remind you that this section is indispensably tied to the article, Working the Plate. The two are inseparable. One is not very useful without the other.

Just a few paragraphs above we defined the strike zone. Knowing what the strike zone is, however, is a far cry from actually seeing it. And with that we leap from the world of measurements and rules to the realm of the umpire-occult. Stay with me, here. The strike zone isn't something that you measure. It's something that you learn to see.

It's not so much the strike zone that you learn to see. Rather, it's the edges of the zone. And you learn to see the calculus of a breaking ball that grazes (or doesn't) the zone peeling in from the top or side, or maybe just clips the bottom as it heads for the dirt. (But watch out for that last one because it will get you in trouble.)

In his insightful article, Advanced Ball & Strike Calling, Peter Osborne argues for building your zone from the bottom up. Others, including Carl Childress (see Working the Plate: Another View, Part 1) argue for building your zone (your mental image of the zone, that is) from the top down.

I'll admit: I'm with Osborne on this one – building the zone from the bottom up. In the article linked to above, there is a section entitled "The Philosophy of the Strike Zone." Far better than I can, Osborne dissects the process of building your zone. Read it. Then read it again. You don't have to agree with everything Osborne says; however, if you don't, you should have a pretty good reason why not. I'm not saying Osborne's advice is gospel; I'm just saying it's really well thought out.

Again, it's a matter of learning to see. Reference points like the knees of both batter and catcher form part of the portrait, as does the movement of the catcher's mitt, the batter's belt, the position of the batter's hands, and of course the plate itself.

See next: Working the Plate.

- Details

- Hits: 156854