Training Umpires, Part 1: Field Mechanics

Over the years I have seen countless umpire training courses, both as an umpire trainee and as umpire instructor. A handful of these training programs and their curricula are quite good, but the vast majority are just horrible. The typical local-league umpire training program lives and dies by PowerPoint presentations, photocopied handouts, and mind-numbing, hours-long presentations that would put an insomniac to sleep. It's slide after slide of field diagrams with arrows and dotted lines and little icons representing umpires and base runners, depicting umpire position and rotations. From this, the aspiring new umpire learns nothing. In truth, less than nothing because sessions like this turn curiosity into confusion.

That’s the first mistake we see in so many umpire training programs: trying to put it all in PowerPoint. I’ve seen 70-slide training sessions that last hours and let’s be honest: retention from such sessions is near zero.

The second mistake is trying to cover it all; that is, trying to condense the breadth of umpiring technique into a single course, trying to turn apprentice umpires into seasoned pros in a weekend. You see this over and over but it’s an approach that’s guaranteed to fail.

Truth: You can teach a new umpire more about umpire mechanics in 30 minutes on the field than you can in six hours in the classroom. Vastly more. And they’ll remember what they’ve learned because they’ve actually done it — they’ve walked through the rotation instead of simply squinting at dotted lines and color-coded arrows on the screen. They’ve heard the pop of the ball in the glove and the sound of the footfall on first base. They’ve had the experience of sprinting from home to third to cover on a first-to-third rotation.

So let’s start by admitting this much: You can’t learn umpiring from a PowerPoint deck. You will only learn by doing it on the field, both in training and in the game, by experiencing it. Experience is your best and your only real teacher.

Learning umpiring is twofold: there's field mechanics, which we're touching on here, and of course there's the rules of baseball -- knowing the rules, and learning how to apply them. We'll have a lot to say about teaching the rules of baseball in Part 2 of this series, but for now let's start off with field mechanics.

Let's be clear, though: What follows is not an attempt to create a training course curriculum. Instead, it's a simple outline of the touch points that any umpire training program needs to hit to enable a new umpire to step onto the field with sufficient competence and a dose of confidence -- enough to get them started on the path to proficiency.

Teaching field mechanics on the small diamond

The two-person crew is the most common configuration in youth baseball. While not ideal, two umpires can manage a baseball game if both umpires understand their roles and responsibilities as well as those of their partner. In any live-ball situation, both umpires must know where they are supposed to be and what they are supposed to be watching. If both umpires are looking at the same thing, then one of them (at least) is screwing up.

Fans in the stands watch the ball. That's how we all learned to watch the game. For umpires, though, that’s wrong. Umpires must learn (must be trained) to watch the game differently. When umpires react to action on a batted ball, one umpire follows the ball (usually the plate umpire (PU), but not always) while the other umpire watches the runner (usually the base umpire (U1), but not always). You’re going to learn who watches what, and when.

Above all, at all times, and umpire must know ...

- What is my proper position at the start of each at-bat (or in some cases, each pitch),

- What signals, if any, should I be exchanging with my partner before the pitch,

- And then, when a batted ball enters the field of play:

- What is my proper rotation (that is, where do I go)

- What should I be watching (the runners or the ball), and

- What calls do I own (and which calls belong to my partner)

That’s the big picture. Any decent umpire training program must, at the very least, instill in the new umpire these fundamentals of field mechanics (where each umpire should be positioned at the time of pitch, where each umpire rotates to on a batted ball in play, what each umpire should be looking at as action develops, and what calls belong to each umpire on the play).

But of course, that's just the beginning.

General responsibilities of the umpires on a two-person crew

The following outlines the responsibilities for each umpire on a two-person crew. This is a short list and covers just the basics but should provide a sound foundation for umpires just starting out. New umpires should experience field drills covering all of these situations.

Plate umpire (PU)

- The PU is the crew chief and manages conduct of the game.

- Carries the official lineup and handles batting order issues.

- Calls balls and strikes on batters.

- Calls plays and rules on infractions at home plate (interference and obstruction, for example).

- Has all catch/no-catch calls, in both the infield and outfield (unless the base umpire “goes out”).

- Has all fair/foul calls on both 1st and 3rd base lines.

- Rules on batted balls and thrown balls that go out of play.

- Has tag-ups and base touches at 3rd in special cases.

Base umpire (U1)

- Calls on all runners at all bases except 3rd in special cases.

- Base touches at all bases except 3rd in special cases.

- Tag-ups at all bases except 3rd in special cases.

- All tag-up and base-touch appeals except 3rd in special cases.

- Check-swing appeals from A and B, as feasible.

- Interference and obstruction on the base paths.

- Rules on thrown balls out of play.

Where I indicate "special cases," these pertain primarily to action on a first-to-third rotation, where the PU covers third base when a runner on first advances to third base. More about this below.

Essential key concepts

There are a handful of core concepts that are fundamental parts of umpiring. These inform the actions of all umpires at all times.

1. Start positions for the base umpire (U1)

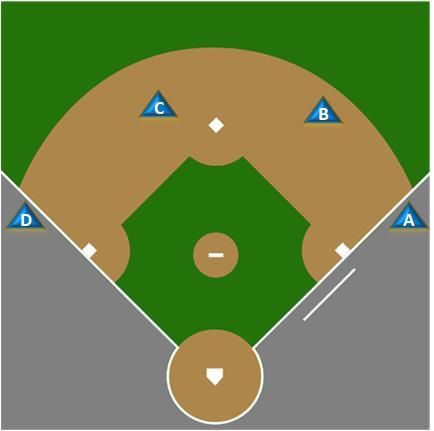

We’ve touched on this already, but let’s get specific. On the small diamond with a two-person crew, the base umpire start positions (A, B, and C) are always outside of the imaginary base paths. (The fourth start position, D, is used only in the three- and four-umpire system.) Base umpires must know instinctively which start positions they should occupy in each of the seven base-runner configurations.

We’ve touched on this already, but let’s get specific. On the small diamond with a two-person crew, the base umpire start positions (A, B, and C) are always outside of the imaginary base paths. (The fourth start position, D, is used only in the three- and four-umpire system.) Base umpires must know instinctively which start positions they should occupy in each of the seven base-runner configurations.

| With no runners on base | U1 starts in A |

| With a runner on first only | U1 starts in B |

| With runners on first and third | U1 starts in B |

| ALL other configurations | U1 starts in C |

Looked at another way (and perhaps easier to remember), there are just three keys:

- U1 starts in A: runner on 1st only, or 3rd only

- U1 starts in B: runner on 2nd only

- U1 starts in C: all other configurations

2. Inside-out / Outside-in

This is a fundamental part of base umpire rotations on a two-person crew: When a fair batted ball goes into the outfield (that is, the batted ball goes outside the base path), the base umpire comes inside, pivots, then stays with the runners.

Conversely, when a fair batted ball remains inside the base paths, the base umpire remains outside the imaginary base path and positions themselves for potential plays on the base runners.

In short: Ball outside: umpire inside. Ball inside, umpire outside.

3. The basic rotations for U1

Let's start here: There are seven base-runner configurations: no runners on (R0); runner on first (R1); runner on second (R2); runner on third (R3); runners on first and second (R1,2); runners on second and third (R2,3); and bases loaded (R1,2,3). Each of these base-runner configurations has U1 in a designated start position, as we've just seen. We also just saw that U1 rotates differently depending on whether a fair batted ball remains in the infield or goes to the outfield (inside-out/outside-in). Therefore, there are two basic rotations for each of the seven configurations depending on whether the ball stays in the infield or goes to the outfield. That adds up to fourteen basic rotations.

As you know, these fourteen rotations do not occur helter-skelter, but rather follow patterns that make them relatively easy to learn. That said, it's important that new umpires understand this, and that they learn to recognize the patterns, and that they learn to respond instantaneously (and correctly) when a batted ball is put in play.

Of course, the plate umpire has rotation responsibilities as well, although far fewer than U1, and these must be addressed in training as well.

4. The working area and the library

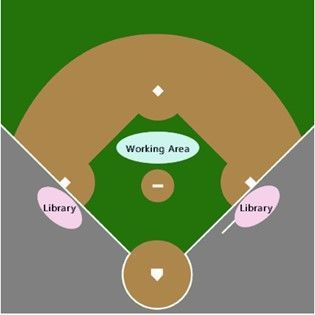

Descriptions of umpire rotations (particularly for U1) frequently refer to two imaginary areas or zones on the ball field where the umpire is directed to move: The working area and the library. Be sure that your new umpires understand these positions and also the extent to which they should be free to range, as dictated by action, within each of these areas.

Descriptions of umpire rotations (particularly for U1) frequently refer to two imaginary areas or zones on the ball field where the umpire is directed to move: The working area and the library. Be sure that your new umpires understand these positions and also the extent to which they should be free to range, as dictated by action, within each of these areas.

The working area is a broad area that lies between the pitcher’s mound and second base, and ranges to the left and right; the working area is somewhat fluid, depending on actions of the base runners. The base umpire will range in this area as dictated by action on the field.

The library (there are two of them) are areas near 1st and 3rd bases, outside the foul lines. In the two-umpire system, only the 3rd-base library comes into play, and then only in situations where the plate umpire is required to rotate up to cover a runner at 3rd base. The library comes into play far more often in three- and four-umpire systems. Note that the image here is a generalized picture of the working area and library. In practice, U1 must learn to range as necessary, as dictated by action on the field.

5. About "going out": Don't

Going out is a rotation where, on a batted ball to the outfield, U1 abandons the infield and sprints toward the outfielder who is making a play on the fly ball in order to have a better view for the catch/no catch call. This is a special-case rotation that comes up when it’s thought the play may be a “trouble ball”; that is, a potential trapped ball that would be very difficult to call from distance. When the base umpire goes out, plate umpire, then, needs to move out into the infield and has responsibility for all runners and all bases.

On the big diamond, and particularly with a three- or four-person crew, going out is standard practice. On the small diamond, however, with only two umpires, I believe that going out makes no sense. Even on a trouble ball. The advantage gained by having a base umpire closer to a trouble-ball call in the outfield is outweighed, in my view, by the disadvantage of leaving the plate umpire alone in the infield with responsibility for all calls at all bases, including home. I should note that my view on this is not universally shared.

Some essential extras

1. Pregame checks and meeting with your partner

Umpire responsibilities begin well before the start of the game. Importantly, an umpire crew must arrive well before game time, ensure that the field is playable (if weather conditions warrant), and the crew must meet to discuss and clarify several aspects of their conduct of the game.

This pregame meeting of the umpire crew is important. Following is a link to a summary of what’s required of the pregame meeting, including a downloadable PDF Checklist of points to cover in the pregame meeting. See the full discussion in the article Pregame Umpire Meeting.

2. Plate meeting with team managers

Rule 4.03 stipulates that the team managers shall meet the umpires at home plate five minutes prior to game time. New umpires need to understand why the meeting takes place and what needs to be accomplished. We have an article, The Plate Meeting, that discusses the subject in detail.

3. Signals, and communicating with your partner

It is essential that members of an umpire crew make eye contact regularly between plays and communicate using a standard set of signals. Signals are the cornerstone of communication among members of an umpire crew and it’s important that new umpires understand the signals and their use.

In addition to the common signals associated with making calls on the field (that is, safe/out, fair/foul, time/play, strike/foul tip, etc.), there is a set of “advanced” signs inside the game (home run, infield fly, catch/no-catch, "it's nothing", etc.). These are also important to understand and learn to use.

On top of these common and advanced signs and signals for events on the field, there is also a set of signals that umpires use to communicate with one another. These include signaling that you’re in an infield-fly situation, or that the umpire is “staying home," or that a time play is in effect.

We have an article that discusses all three of these signal categories entitled Umpire Signs & Signals to help acquaint new umpires with protocols for communicating on the field.

Wrapping up

The goal in training new umpires is not to overwhelm, but rather to provide enough of the fundamentals to give them the confidence they need to handle themselves competently on the field. Expertise will come with time and experience. What they need at the outset is basic competency, a bit of confidence, and a fair dose of chutzpah.

In Part 2 of our series on training new umpires we’ll discuss teaching umpire students about the rules of baseball.