Rules

Pitcher's Mound and Dimensions

Pitcher's Mound and Dimensions

Umpiring various age levels and leagues, you are exposed to a variety of pitching dimensions. "Regulation" dimensions (those used in professional baseball, college, high school, and most amateur leagues whose players are about 14 and older) use a field composed of 90-foot base paths and a pitching distance of 60'-6" from the front of the pitcher's plate to the point at the rear of home plate.

Most youth leagues, however, use a variety of field dimensions and pitching distances, depending on the league and the age level of the players. Following is a summary of the most commonly used field dimensions.

Field dimensions in amateur baseball

Following are the most common pitching and field dimensions.

- Regulation field. As we've said, on a regulation field the pitching distance is 60'-6". The distance from base to base (the base path) is 90'. Regulation fields are used in professional baseball, of course, but also in college, high school, and most youth leagues whose players are about 14 and older.

- 54/80. Pony Baseball's Pony division (13-14 year olds) play on fields whose pitching distance is 54 feet and whose base paths measure 80 feet.

- 50/70. Little League introduced a new "Intermediate" division in 2012 for players from 11-13 that uses a 50-foot pitching distance and 70-foot base paths. Cal Ripken also has a 50/70 division for 11-12 year olds, and Pony Baseball uses these dimensions for its Bronco division (11-12 year olds).

- 46/60. A pitching distance 46 feet (with 60-foot base path) is standard for Little League divisions where the players are 12 and under. These dimensions are also common for other youth leagues whose players are 12 and under.

Note: Umpire field mechanics on playing fields measuring 50/70 and larger tend to be consistent, so throughout we will use the term "big diamond" to refer collectively to fields that are 50/70 and larger. Mechanics on 46/60 fields, however, are quite different, so we'll refer to 46/60 fields as "small diamond."

The pitcher's mound

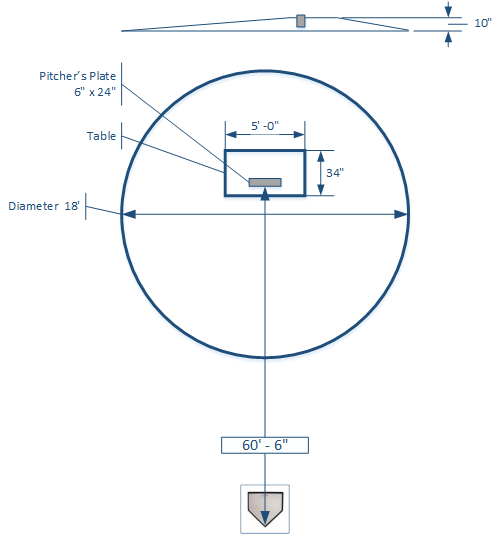

On a regulation baseball diamond, the pitcher's mound measures 18' in diameter. The flat area atop the diamond, called the table, measures 5 feet wide by 34 inches deep. Six inches from the front edge of the table is the pitcher's plate (also called the rubber), which measures six inches deep by 24 inches wide.

The distance from the front edge of the pitcher's plate to the rear point of home plate measures 60'-6". This distance was established in 1893 and has served baseball well for 125 years. The height of the mound, however, has changed – most recently in 1969, when it was lowered to its present height of 10 inches. From the front of the table, the mound slopes down such that it loses one inch of height for every foot nearer to home plate.

These dimensions are the ideal, of course, and on professional fields an army of groundskeepers do well to maintain the proper dimensions. But a pitching mound is a difficult piece of ground to maintain, and on amateur fields you are most often lucky to see a mound that is wholly conforming to the regulations.

- Details

- Hits: 155839

OBR / NFHS Rules Differences

OBR / NFHS Rules Differences

Working across multiple rule sets is always a challenge, but never moreso that managing the differences between American high school rules (National Federation of State High School Associations), or NFHS (also referred to as FED), and the Official Baseball Rules (OBR), To make it easier to review the rules differences, we've broken the rules down into seven categories:

Administrative rules

- Proper Appeals: Live ball/Dead ball

- Substitutions: Re-entering starters

- Substitutions: Illegal substitute

- Game ended by darkness or weather: Suspended vs. ended game

- Shortened game: Mercy rule

- Umpire touches or handles live ball

- The umpire's jurisdiction begins when …

- Guidelines on correcting umpire errors

Batting rules

- Appeal on checked swing

- Backswing interference / follow-through interference

- Designated hitter (DH)

- When does runner abandon effort to advance on 3rd strike not caught

Coaching rules

- Defensive conferences (visits)

- When is a defensive visit concluded

- Offensive conferences

- Base coaches

- Disciplinary actions against coaches

Fielding rules

- Obstruction

- Ball lodged in clothing or equipment

- Fake tag without the ball

- Catch and carry

- Player positions on the field

Pitching rules

- Actions allowed from windup position

- Balks

- Illegal pitch (no runners on)

- Pitch count limits and rest requirements

- Feint to third base / 3-1 move

- Time limit to deliver pitch

Base running rules

- Legal/Illegal slide; force-play slide rule

- Must slide or attempt to avoid

- Collisions with defender / malicious contact

- Courtesy runner

- Diving over defender

- Running lane interference

- Walk-off scoring

Equipment rules

- Legal bats / bat regulations

- Catcher's mitt

- First baseman's mitt

- Fielding gloves

- Details

- Hits: 61623

Pre-Game Meeting Checklist

Pre-Game Meeting Checklist

Prior to every game, you and your partner must take five or ten minutes to discuss a handfull of issues that are essential to effective teamwork. Do this before every game, even if you've worked with your partner numerous times.

This checklist will help ensure that you don't overlook something important in your pregame meeting. The UmpireBible checklist is adapted from several sources (so it's not original, just useful) and touches on all of the essential topics you need to cover.

Prior to game and on arrival at the field

- Confirm assignment, game time, field, parking location, colors. Use email or phone your partner at least a day ahead of the game (preferably two days in advance). If your association does not assign slots, then arrange who takes the plate/bases. Arrange to park together so you can conduct your pregame meeting while preparing for the game. Agree on colors (by tradition, the plate umpire calls the shirt color).

- Arrive at the field at least 30 minutes before game time. Recommended: arrive one hour before game time.

- Check in with tournament director, coaches, or athletic director. Make certain that the person in charge of the game is aware that you have arrived. For most games this will be simply the home team manager. In tournaments there is either a tournament director or a tournament umpire coordinator.

- Check condition of the field.

If weather is a factor, be sure to check the condition of field to ensure that it's playable. If there are issues, discuss this with the person in charge (likely a coach or athletic director). They can cancel the game at this time. Once you have exchanged lineups at the plate meeting, however, the game belongs to you and you are the sole judge of the playability of the field.

Pregame meeting with your partner

- Catch/no-catch coverage. This will vary depending on whether you are on the big diamond or small diamond, as well as on the size of the crew. Go over all catch/no-catch coverage scenarios. Be sure to cover your infield scenarios, too. For detailed information, see Catch/No Catch and Going Out.

- Fair/foul coverage. With a two-man crew, this only comes into play with U1 in the A position.

- Signals & eye contact. Run through the signals you'll be using through the game to ensure the crew are all on the same page. PU initiates signals and base umpire(s) return. For more information, see the article Umpire Signs & Signals.

- Checked swings. Discuss handling checked swings and "going down" on appeal.

- First-to-third rotation. When you have R1 or R1 and R3, on batted balls to the outfield the PU has R1 into 3rd base and beyond. Go over this and also cover the signal you'll use when you get into a first-to-third situation.

- Touches and tags at 3rd (with runners on). Be sure to cover that with runners on base the PU has all touches and tags at third base. If there is an appeal at third base in this situation, the PU rules on the appeal.

- PU rotations. Cover PU rotations – when staying home, when going to third, and when he has the catch/no-catch.

- U1 Going out. Discuss U1 "going out." On a two-man crew this will only happen from the A position; with three- or four-man crews you must discuss and clarify the scenarios. For more information see our article Going Out.

- Rundowns. Discuss mechanics of partner coming up to "get this end" of a rundown.

- Calling balks. If this applies to your level, discuss covering balk calls.

- Foul ball off the batter in the box. Often seen more clearly by U1; discuss "see it, call it."

- Overthrows out of play. Technically, overthrows out of play belong to the PU; however, this is another "see it, call it."

- Running lane interference. Again, the PU owns this call; however, especially with a runner on third, U1 might grab the call. Cover communicating that "I've got this one" if you switch up a call like this.

- Force-play slide violation/interference. Discuss the force-play slide rule for your league (this rule varies) and emphasize that PU needs to have eyes on runner going into second when there's a double-play attempt in progress.

- Swipe tag / pulled foot at 1st base. Discuss PU either trailing runner (enless other runners in scoring position), or watching from 1st base line extended (1BLX) to help with swipe tag and pulled foot at first.

- Appeals, touches, tags. Discuss who owns touches and tags at the bases in all scenarios. The owner of a given base also owns any appeal at that base. While base umpire(s) typically own all runners at all bases, there are situations where the PU has 3rd base, or, if U1 goes out, PU has the runner all the way.

- Getting the call right. Discuss your mechanics for getting together if you have a questionable call or a coach's appeal of an error in the application of a rule. Never conference on judgment calls unless you're pretty sure you screwed up and want some cover to reverse the call.

- Equipment inspection (Little League only). Little League is the only league (that I know of) where umpires are required to inspect bats and helmets to ensure they are rules compliant. Discuss to ensure that you understand the bat regulations for the game's age level.

- "I have information for you". Occasionally you will see something on partner's call that might help him on a disputed or controversial call. If so, never intrude on your partner's handling of the call. However, you can have a prearranged signal to indicate (subtly) that you've seen something he might like to hear about. If you make eye contact, flash the signal and then your partner can decide whether to conference with you.

- Details

- Hits: 30725

Force Play Slide Rule / Illegal Slide

Force Play Slide Rule / Illegal Slide

There has long been a force-play slide rule at most levels of amateur baseball, and at all levels there is a clear definitions of legal vs. illegal slides. The potential for collisions and serious injuries, as well as for malicious behavior, is so prominent in sliding (particularly in force-play and potential double-play situations) that amateur baseball, from Little League through NCAA, enforces strict rules. Only recently has Major League Baseball followed suit (see the blog post, MLB’s Chase Utley Slide Rule & Demise of the “Neighborhood” Play).

Force-play/slide rules differ across the various leagues. We'll cover the following:

Force-play/slide rules differ across the various leagues. We'll cover the following:

But before going on, let's debunk a common misconception about slide plays in general, and the force-play slide rule in particular: There is no requirement (in any rule set) that a player must slide. This myth seems impossible to kill as coaches bring it up constantly. Sliding is discretionary. Period.

That said, if a player elects to slide, the slide must be legal. This applies in all rule sets.

NCAA (college) slide rule

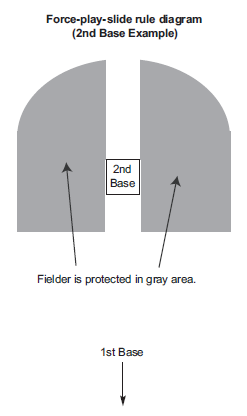

The NCAA slide rules are captured in NCAA Rule 8-4 (from which the image above is taken). In my view, NCAA provides the most sensible and common-sense approach. In a nutshell:

- On a force play, the runner must slide on a line directly between the bases; it is allowable to slide through the base if the runner's momentum carries him beyond the bag.

- If carried through the bag, contact with the defender beyond the bag is allowable so long as the slide is legal in all respects. Note that contact "on top of" the bag is legal, even if the slide is a "pop-up."

- A runner may slide to either side of the bag so long as he chooses a side away from the fielder and avoids making contact or altering the play of the fielder.

- Rule 8-4(c) outlines the five actions that make a slide illegal.

- The Penalty section outlines penalties for each of the five illegal slides. Note that the penalty section (3) stipulates that an umpire can judge a runner's slide or resulting collision to be "flagrant"; in such cases, the offending runner is to be ejected.

Note that NCAA also has a strict rule regarding collisions at home plate. See NCAA Rule 8-7 (the "collision rule").

NFHS (high school) slide rule

The NFHS rule book first defines legal and illegal slides in NFHS Rule 2-32. It further rules on illegal slide behavior in Rule 8-4-2(b). The NFHS rule is more restrictive than the NCAA rule:

- As with NCAA, high school players must slide "on the ground and in a direct line between the two bases," or "within reach of the base with either a hand or a foot" on the side of the base away from the fielder.

- Significantly, the runner is out if he slides beyond the bag and "makes contact with or alters the play of the fielder." In other words, contact is not required if the runner slides past the bag and "alters the play of the fielder." However, the runner is allowed to slide through and beyond the base at home plate.

- The rule goes on to list actions that make a slide illegal, including kicking or slashing at the fielder, raising a let higher than the fielder's knee, and so forth.

Related NFHS rules:

- Rule 2-21-1(b) – Malicious contact (offensive interference).

- Rule 3-3-1(n) & Penalty – Malicious contact; offender ejected

Little League slide rule

The Little League slide rule is captured in Rule 7.08(a)(3-4).

Again, there is no "must-slide" rule in Little League. The rule simply states that runners must either "slide or attempt to avoid" a fielder with the ball who is attempting to make a tag. Of course, the runner is free to reverse direction.

For malicious or injurious action on the part of the runner (taking out the catcher, for example), Little League relies on unsportsmanlike conduct rules to penalize malicious behavior; there is no "malicious contact" rule as such.

Pony Baseball slide rule

Pony baseball plays OBR with added safety rules. Surprisingly, though, Pony provides no safety rule around sliding on force plays or potential double plays. Therefore, OBR Rule 6.01(j) applies to all levels of Pony baseball.

Major League Baseball slide rule

Major League Baseball has recently readdressed the issue of ensuring safety for middle infielders on double-play attempts in OBR Rule 6.01(j), as well as collisions at home plate in OBR Rule 6.01(i).

MLB begins by defining a "bona fide slide" in 6.01(j), and then outlines actions contrary to a bona fide slide that constitute interference. A bona fide slide requires that the runner:

- begins his slide (i.e., makes contact with the ground) before reaching the base;

- is able and attempts to reach the base with his hand or foot;

- is able and attempts to remain on the base after completion of the slide (except at home plate); and

- slides within reach of the base without changing his pathway for the purpose of initiating contact with a fielder.

A runner, then, is exempt from being called out for interference so long as the slide is bona fide; nor shall a runner be liable for interference if the fielder is positioned in the runner's "legal pathway to the base."

The runner loses his exemption from interference if he "intentionally initiates (or attempts to initiate) contact with the fielder by elevating and kicking his leg ...," or by throwing a "roll block."

Contact with the fielder is allowed so long as it occurs within the context of a bona fide slide, and so long as it does not include deliberate actions intended to disrupt a play by the fielder.

- Details

- Hits: 88455