Rules

Foul Ball / Foul Tip

Foul Ball / Foul Tip

I have a pet peeve. Like you, I enjoy watching professional baseball on TV. But nothing irks me more than commentators who call a foul ball a foul tip. Joe Buck is the worst offender, but there are others. Any sharp foul ball that shoots straight back over the catcher's shoulder or off the umpire's mask or otherwise goes uncaught but sharp off the bat, these dingbats call it a foul tip. These are not foul tips, they're foul balls.

Foul balls and foul tips are two distinctly different things. One results in a dead ball, the other is a live ball. One can result in strike three, the other cannot. One of them, by definition, must be caught; the other, again by definition, must not be caught. Foul balls and foul tips could not be more different.

In this article we cover the following:

Let's talk about the foul tip first, because it's the most straightforward.

What is a foul tip

First off, let's look at the rule-book definition of a foul tip [Definitions (foul tip)]. I'm going to add some boldface and italic for emphasis:

"A FOUL TIP is a batted ball that goes sharp and direct from the bat to the catcher and is legally caught. It is not a foul tip unless caught and any foul tip that is caught is a strike, and the ball is in play."

NOTE: The 2021 edition of the OBR changed the definition of foul tip. Whereas previously the definition read "a batted ball that goes sharp and direct from the bat to the catcher's hands ...," the 2021 update changed "to the catcher's hands" to read, simply, "to the catcher." The change also removed the following sentence: "It is not a catch if it is a rebound, unless the ball has first touched the catcher's glove or hand."

The upshot, then, is this: Any batted ball that goes sharp and direct from the bat to the catcher (any part of the catcher) and is legally caught is a foul tip. It is no longer required that the tipped ball touch the catcher's hand or glove first. A rebound off the mask or chest, for example, qualifies as a foul tip so long as the ball rebounds directly to the catcher's hand or glove and is legally caught.

Okay, now plainspoken:

- A foul tip is a pitched ball that skips off the bat and goes "sharp and direct" to the catcher "and is legally caught." That the ball is caught is the cornerstone of the definition of a foul tip. A ball that is not caught by the catcher is not (and cannot be) a foul tip.

- A foul tip is always a strike; and, unlike a foul ball, a foul tip can result in strike three.

- A foul tip is a live ball. Runners can advance (steal) at their peril.

- If the catcher does not catch the ball, then it's a foul ball (dead ball). Period. For clarity, let's call this a tipped foul ball.

- When a tipped batted ball is caught by the catcher after the ball hits his mask (for example), his chest, or anything else, this IS a foul tip (according to the 2021 rule change noted above).

- If a tipped batted ball hits the umpire first and then rebounds and is caught, the is NOT a foul tip, nor is it a fly-ball out. The instant the ball touches the umpire in foul territory, it becomes a foul ball/dead ball. (It's the same as a fly ball that hits a backstop or fence or anything else (except the catcher) in foul territory.)

- The mechanic for a foul tip is to brush the back of your left hand with your right hand, then give the strike signal. Some umpires swipe the back of their left hand two or three times, then give the strike signal.

What is a foul ball

Definitions (foul ball) begins with the longest, most poorly written and awkwardly tortuous sentence in the entire rule book, and also includes an extended "comment." I won't repeat it here, but ...

Again, plainspoken:

First off, there are three foul ball scenarios (and one special case) and you judge the ball to be fair or foul differently for each scenario:

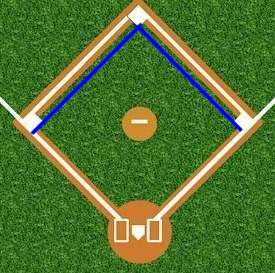

- Batted ball inside the bags. By this I mean a bounding or fly ball that stays or falls inside an imaginary line that's drawn around the infield at the front edge of the bases, but does not touch the bases. On the image below, picture the blue line as a sheet of glass enclosing the area we call "inside the bags."

Judged fair or foul by the position of the ball when (a) first touched by a fielder, or (b) where the ball comes to rest. It is not uncommon for the ball to fall in fair territory and then spin into foul territory before it is touched (or the other way around). On balls inside the bags, you must wait until the ball is either touched or comes to rest before judging it fair or foul. Until then it's nothing, so don't rush that call.

- Bounding ball beyond the bags. A "bounding ball" is a batted ball that touches the ground (bounces) at least one time before it reaches the blue line that defines the area "inside the bags," but then bounds beyond the blue line (breaking the imaginary glass).

Judged fair or foul by where it crosses (and breaks) the blue sheet of glass. It the bounding ball crosses the sheet on or over the bag (that is, breaks the glass), then this is a fair ball. However, if the bounding ball passes the blue sheet in foul territory (and does not break the glass) then it is a foul ball, despite the fact that it may have bounced one or more times in fair territory before reaching the blue sheet.

- Fly ball beyond the bags. We're talking here about any batted ball that passes over the blue line in flight. It does not matter whether it crosses the blue sheet in fair or foul territory. It only matters where the ball first touches the ground or is first touched by a fielder.

Judged fair or foul by where the fly ball first touches the ground, or where a fielder first touches the ball in flight. If the ball first touches the ground in fair territory, it is a fair ball. If in foul territory, then it's a foul ball. Similarly, if a fielder first touches the ball while the ball (not the fielder) is over fair territory, then it's a fair ball. Likewise, if first touched over foul territory, it's a foul ball.

- Special case: Batter hit by his own batted ball while still in the batter's box [ 5.09(a)(7) ]. So long as the batter is still in the batter's box, any batted ball that strikes him is simply a foul ball (not interference). Sometimes the ball goes directly from the bat to the leg or foot (ouch!); other times, it bounces on or near the plate and then bounces and strikes the batter. That's still a foul ball. Of course, once the batter steps out of the batter's box, any batted ball that touches him is interference and he is out.

Judged fair or foul. The only judgement is whether the batted ball hit the batter while he is still in the batter's box. If it did, then you have a foul ball. Come up fast, big and loud: "FOUL! FOUL!" This call belongs to any umpire who sees it.

This is sometimes difficult to see, particularly for the plate umpire. It can also be tricky because sometimes a batted ball will hit off home plate and come out oddly, making it look like it came off the batter's foot. Experience alone will help you see this clearly. Along with experience comes the ability to infer certain things from the batter's actions. Be careful with this because, at upper levels particularly, batters will try to manipulate you with their acting skills. At lower levels, however, the batter's reactions run truer.

A few important points about foul balls

- Foul lines are fair territory. So is the foul pole, first and third bases, and home plate. If a batted ball comes to rest with any part of the ball in fair territory, it's a fair ball.

- If any part of the ball is over a foul line it's a fair ball. On a ball that comes to rest in contact with the foul line, it is a fair ball if any portion of the ball is over the foul line. Of course, this also applies to a ball that is in motion and is first touched by a fielder while the ball is over the foul line. That said, this latter case is nearly impossible to see in real time, especially if the fielder is running hard toward foul territory to field the ball. That is one of the most difficult judgment calls in baseball.

- The position of the fielder has no bearing on whether a ball if fair or foul. Unlike football, it does not matter whether the fielder who first touches a ball is in fair territory or foul. The judgement of fair/foul is based entirely on the position of the ball relative to the foul line.

- A batted ball becomes foul (and a dead ball) the instant it touches the backstop, a fence, or any other structure, person (e.g., the umpire) or player while over foul territory.

- A fly ball that is caught in foul territory is not a foul ball. A foul ball, by definition, touches the ground, a fixture, or a person in foul territory. A fly ball caught in foul territory is simply a fly ball out; the ball is live and runners may advance (at their peril) after tagging up.

- A batter-runner who intentionally deflects a ball that is in foul territory should be called out, the ball is dead, and other runners, if any, may not advance [ 5.09(a)(9) ].

- An infield fly is waved off if the ball drops uncaught in foul territory. When calling an infield fly that is close to the foul line, you signal and verbalize loudly "INFIELD FLY IF FAIR!" If the ball drops uncaught in foul territory, or is first touched (but not caught) by a fielder in foul territory, it is no longer an infield fly but just a foul ball and the batter is not out. Of course, if the ball is caught this is an ordinary caught fly ball out: the batter is out but the ball is live and runners may advance after tagging up.

Mechanics for calling a foul ball

The basics

In our articles on Umpire Mechanics we'll discuss at length which umpire owns the fair/foul call, when and where. For now, let's concentrate on the mechanics.

You verbalize a foul ball ("FOUL!") and raise both arms, palms forward. For a foul ball in the outfield you then point in the direction of the foul.

You never verbalize a fair ball. Instead, you simply point into fair territory. If the call is a close one, point emphatically.

Beyond the basics

Using the basics for a foundation, amend your mechanics as follows:

- On a "stadium call" you do not need to signal nor verbalize a foul ball. What's a "stadium call"? It's a call that a spectator could accurately make from the top row of the nosebleed section at Yankee Stadium. It's a ball that sails ten rows into the stands, or that shoots up behind the backstop and lands on a car in the parking lot.

- Only one umpire should ever make the initial fair/foul call. Everyone on the crew (whether two, three, or four) should know which umpire has responsibility for any given batted ball. Be sure to discuss this at your pregame meeting to ensure you're all on the same page with regard to fair/foul responsibilities. We'll talk about this more in Umpire Mechanics. Once the initial foul call is made, however, other umpires on the field should echo the call if necessary to stop action on the bases.

- Details

- Hits: 217645

Designated Hitter / Extra Hitter

Designated Hitter / Extra Hitter

Implemented in the American League in 1973, the Designated Hitter (DH) rule has migrated to most levels of amateur baseball, but in somewhat different forms. While OBR Rule 5.11 provides for a designated hitter to bat for the pitcher (and only the pitcher), most DH rules in amateur baseball leagues allow the DH to bat for any defensive player.

The original intent of the Major League rule was to enhance offense in the game (and to protect some aging players); however, amateur versions of the DH rule are also intended to increase opportunities for players to get in the game. It is this latter point that has led to yet another innovation, which you see only in amateur baseball, the "extra hitter" (EH).

Designated hitter (DH)

I won't try to summarize all of the DH rules for all of the leagues. That would require a small book. Instead, I'll present a list of key features of the DH rule and point out where other rule sets are likely to differ. Of course, the key point here is that you must learn the DH rule for the league (or leagues) for which you work.

- The DH is a player who is in the lineup, but who does not play on defense. In the Major Leagues (the American League), the DH, by rule, bats only for the pitcher. In most amateur leagues, however, the DH can bat for any defensive player. The net result is that the batting order lists ten players, but only nine of these players bat. Be sure to track the player (the tenth player) for whom the DH bats.

- Using the DH is optional. In leagues where the DH is allowed, teams are not required to use a DH. This can be a game-to-game manager's decision.

- The DH must be declared on the starting lineup. The DH must be on the starting lineup presented to the plate umpire at the plate meeting prior to the start of the game. If a team begins a game without a DH, they may not add one to the lineup after the lineups become official at the plate meeting.

- If the DH later enters the game defensively, he keeps his place in the lineup and the pitcher (or other player for whom he's batted) takes the spot in the lineup that was occupied by the player the DH just sub'd in for. Important: Whenever the DH enters the game defensively, the DH position is terminated for the remainder of the game.

- You can substitute for the DH. If you start the game with one player as your DH, you can later sub in another player into that spot in the batting order, and that player becomes the DH. You can make this substitution either on offense (as a pinch hitter or pinch runner), or on defense, as a straight-up substitution.

- The player listed as the DH on the starting linup must bat at least one time before being substituted for. There are two important exceptions to this rule. (1) If the DH is injured (or ejected, for that matter), you can sub in another player. (2) If the opposing team changes its starting pitcher before the DH has his first at-bat, you can legally sub in another player at the DH position.

This is all pretty straightforward. Where it gets messy (and where many leagues go their own way) is in the matter of substitutions involve both the DH and the pitcher. It gets so messy, in fact, that the NCAA requires (by regulation) that at least one umpire on each crew has to carry a laminated cheat sheet to help them negotiate the subtleties of pitcher/DH-related substitutions.

Extra hitter (EH)

The extra hitter (EH) rule takes the concept of the designated hitter one step further. Instead of just adding a player to bat for a defensive player (ten players, but only nine batters), the EH adds a tenth batter to the batting order. If a team is playing with both the DH and the EH (this is not uncommon), then you have eleven players in the lineup, ten of whom bat.

Of course, the EH rule is not a rule that you'll find in the OBR, and is not used in Major League play. The impetus for the rule is simply to more easily involve a greater number of players in the game, and is particulaly common in youth leagues. Because of that, EH rules are league-level and may vary from league to league. The EH rule generally stipulates the following (but again, you must check your league rules):

- The EH must be declared on the starting lineup. An EH cannot be added to the lineup after lineups become official at the plate meeting.

- The EH may bat in any spot in the batting order. However, the EH spot in the batting order may not change during the game. That is, if you have the EH in the three-hole at the start of the game, the EH remains in the three-hole for the entire game, irrespective of substitutions into and out of the EH slot.

- The EH is eligible for substitution and re-entry into the game. Whatever substitution and re-entry rules are in effect for the league and level, these rules apply equally to the EH. This means you can sub in a new EH during the game, and in most cases re-enter the original EH later in the game

- The EH may be entered into the game defensively. Combined with the free re-entry rule, this means that a manager can make defensive moves that include the EH, including swapping a defensive player for the EH, whereupon the defensive player that was just swapped out can become the new EH. In short, the manager can shuffle his ten players in the batting order (excluding the DH, of course, if also in the game) among the nine defensive positions. These are defensive swaps, not substitutions.

- The EH role may not be eliminated during the game. Once you start with an EH, you must keep the EH for the entire game. The only exception is if your team drops to only nine players due to injury, ejections, or players leaving early.

There are some loose ends on the EH rule, and variation from league to league (and level to level) so it's essential that you be fully briefed on the rule for the league you work.

- Details

- Hits: 120742

Batter Touched by Live Ball

Batter Touched by Live Ball

You should read this article in alongside its companion, Runner Touched by Live Ball. Originally I had just one article that covered both batter and runner because there is so much overlap. However, because the rule book differentiates between the batter, the batter-runner, and then the runner, I've broken them up.

Let's start by breaking the batter portion into its two main parts:

1. The batter touched by a pitched ball

2. The batter-runner touched by his own batted ball

Because you handle each case differently, well go deep on both. First, though, keep in mind that when we talk about a batted ball, we're talking about a live batted ball. A batter-runner touched by a batted ball over foul territory is just a foul ball (unless he intentionally deflects it [see 6.01(a)(2) ]).

Batter touched by pitched ball

Let's start with a batter hit by a pitched ball. We all know that if a batter is hit by a pitch he is awarded first base (and that other runners advance if forced). Right? WRONG!

In truth, most often it is the case that a batter is awarded first base when he or his clothing is touched by a pitched ball. But not always. Let's look at some exceptions and nuances of the rules covering batters touched by a pitched ball:

- The originating rule is 5.06(c)(1). A batter in a "legal batting position" (that is, with feet in the batter's box) is awarded first if he or his clothing is touched by a pitched ball. The ball is dead. Runners on base advance if forced.

- But hold on a minute. In 5.05(b)(2) we get our first exceptions – actually, two exceptions. The first is, if the pitch is in the strike zone when the batter is hit, he is not awarded first base. You see this when batters crowd the plate and their arms and hands are out over the strike zone. The ball is dead, but call a strike and keep the batter at the plate (unless it's strike three). Any runners who were advancing on the pitch must return to their time-of-pitch base. And be ready for some arguments.

- The second 5.05(b)(2) exception requires that the batter must attempt to avoid being hit by the pitch. Now, this one is tricky. The move to avoid the pitch can be as subtle as a quarter-turn away from the pitch. If there is no attempt at all to avoid the pitch, by rule you keep the batter at the plate. That said, there is some discretion in cases where the pitch is well into the batter's box. In that case, most umpires give the batter the benefit of the doubt and award him first base regardless. But be careful with that.

And watch out for this one: You'll see some of the older, more experienced batters do that quarter-turn away from the ball, but what they're really doing is slyly moving into the path of the pitch as they make that quarter-turn. It's subtle, and it's easy to get fooled (I've been fooled by this). You won't see this in the younger kids (most of them are too afraid of the ball to begin with), but you can run into this at the upper levels.

- The exception that surprises some new umpires (and players) is the 5.09(a)(6) exception. This is the rule saying that if you are hit by the pitch while swinging at it, it's just a strike. No base award; just a strike (and the batter is out if it's strike three).

Caution: If you have a batter hit by pitch on a checked swing, be alert. If you rule that he went (or if you go to your partner and your partner says "Yes, he went"), then you have a strike (and the batter's out if strike three). If you or your partner rules that "No, he didn't go" then you have a batter hit by pitch and a base award. Be alert for this.

We have an MLB video that captures just this scenario. Miguel Cabrera checks his swing on a pitch that hits him square in the knee. Home plate umpire, Brian Gorman, rules that he went, so instead of hit-by-pitch, it's a strike. Cabrera grouses and is eventually tossed.

- Let's be really clear about one thing: Regardless of all other circumstances, a batter touched by a pitched ball is always a dead ball, regardless of all other circumstances. Whether there's a base award or not, the ball is dead and no other runners can advance unless forced.

- Finally, let's touch on the subject of batters who are hit by a pitch intentionally [ 6.02(c)(9) ]. This is a judgment call, of course, but if you suspect there's intention, you must deal with it immediately and firmly. Fortunately you have tools – not just under 6.02(c)(9), but also under 8.01(d) (unsportsmanlike conduct).

- Warn the benches. If you suspect a pitcher of head-hunting, call "Time" and warn both benches. (If you warn the bench of one team you must also warn the other.) Subsequent incidents should result in ejection.

- If you believe there is a serious issue of organized head-hunting, eject the pitcher. If necessary, you can also eject the manager, either at the same time, or subsequently.

In rare situations where, for example, rival teams appear particularly hostile as they prepare for the game, you have the authority to issue the bench warnings preventively at the start of the game.

Batter touched by his own batted ball

A batter touched by his own batted ball is either (1) the batter is still in the batter's box when the ball rebounds and hits him or the bat, or a batted ball hits him directly on the foot or ankle, or (2) he is touched by a fair batted ball after he's left the batter's box.

In the first scenario, where the batter is hit by his own batted ball while still in the box, this is simply a foul ball [ 5.09(a)(7) ]. Sometimes it's difficult for the plate umpire to see this, so the base umpire(s) should immediately call "Foul" if they see it.

In the second scenario, where the batter is touched by his fair batted ball after he's left the batter's box, you have interference. The batter is out, the ball is dead, and runners, if moving, must return to their time-of-pitch base. This is no different from other base runners touched by a fair batted ball, which we discuss in the article Runner Touched by Live Ball.

Note that if the batter is touched by the ball over foul territory, that's simply a foul ball, not interference (unless the runner intentionally deflects the batted ball [6.01(a)(2)]).

Here's a video showing an example of a batter being hit by his own batted ball – in this case, on a bunt attempt. You can see that he runs into his own batted ball as he leaves the batter's box. That's interference. No arguments on this one.

- Details

- Hits: 87198

Batting Out of Order

Batting Out of Order

Few baseball rules are dealt with incorrectly more frequently than batting out of order. The applicable rule is 6.03(b), which was last revised (and clarified) in 1957. So the rule has been around for a while.

The rule, penalties, and remedies for batting out of order are not difficult to understand. The tricky part is fixing a batting-order infraction once an appeal is upheld. The plate umpire owns this one since the plate umpire owns the lineup.

Note: For an interesting read about the history and confusion surrounding this rule, see an article in the SABR Research Journal entitled, fittingly enough, Batting Out-of-Turn Results in Great Confusion, written by Mark Pankin.

Let's start by clarifying two terms essential to discussing batting out of order: proper batter and improper batter.

- Proper batter. The correct batter at bat with respect to the official lineup. To belabor the obvious, there is always just one (and only one) proper batter at any given time.

- Improper batter. Any offensive player other than the proper batter who is at bat.

When untangling a batting-order infraction, only two batters matter: the batter who is presently at bat, and the player who batted previously. We'll see why shortly.

Important: Batting out of order is an appeal play. You should never point out an improper batter on your own initiative, nor should you let the scorekeeper or anyone else "outside the fence" have any say. Only members of the team on defense can ask for time and appeal a batting order issue, although the offense can ask for time and rectify the mistake while the improper batter is still at bat.

The Appeal

A batting-out-of-order appeal begins with the defense asking for time. The manager approaches the plate umpire and claims there is a batting-order infraction. At this point you consult the the official lineup (which is the one that you carry) to establish whether a player batted (or is batting) out of turn.

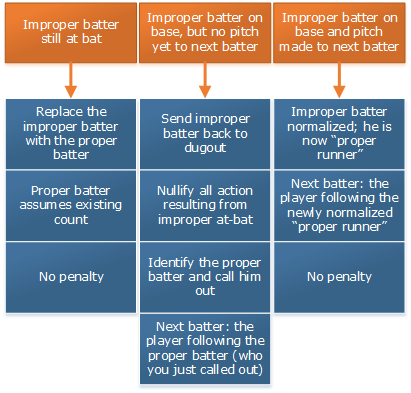

A batting order infraction presents itself in one of three ways:

- An improper batter is currently at bat and has not completed his turn at bat.

- An improper batter has completed his turn at-bat, and a pitch has been thrown to a batter following the improper batter.

- An improper batter has completed his turn at bat, but a pitch has not yet been delivered to a following batter.

Note: Frequently, what appears to the defense to be a batting-order infraction turns out to be confusion caused by an unannounced substitution [ 5.10(j) ] Be alert for that.

Remedies and Penalties

If upon consulting the lineup you confirm that any one of the three cases applies, you have a batting-order infraction and you should uphold the appeal. You must then take one of three courses of action, depending on which of the three cases applies.

- The improper batter is still at bat. If you confirm that the player currently at bat is an improper batter, you must do two things:

- First, send the improper batter (who is currently at bat) back to the dugout.

- Next, call the proper batter to the plate. The proper batter assumes the count (if any) that was on the improper batter. That's it. Play on. There is no penalty if the infraction is discovered while the improper batter is still at bat, or until a pitch is delivered to a batter following the improper batter.

- A pitch has been delivered to the batter following the improper batter. If you confirm that an improper batter has just completed a turn at bat and the following batter, who is now at the plate, has received one or more pitches, the defense is out of luck. Once a pitch is delivered to the batter following an improper batter, then the improper batter (whether on base or in the dugout, if he's been put out) is now "normalized." That batter is now (retrospectively) the proper batter. The lineup, then, continues with the newly normalized batter and follows the official lineup from there. Important: The matter of normalizing an improper batter, and then establishing the correct batting order moving forward, is where a lot of mistakes are made.

- The improper batter has reached base or otherwise completed his at-bat. If you confirm that an improper batter has completed his turn at-bat (and either reached base by any means, or has been put out) but there has not yet been a pitch delivered to the batter following the improper batter, then take the following steps:

- First, consult the lineup and identify the proper batter (the player who failed to bat in his turn in the lineup); call that player out. (You do not call out the player who batted improperly, rather. it's the player who failed to bat in his turn that you call out. This is another common mistake.)

- Next, nullify any action that resulted from the improper batter's at-bat. If the improper batter is on base, you must send him back to the dugout. If other runners advanced as a result of his at-bat, return those runners to the base they occupied when the improper batter advanced. If the improper batter was put out, the out is also nullified and comes off the board. (Note: If a runner advanced by stealing a base during the improper at-bat, that runner's steal stands.)

- Finally, call the next batter to the plate. The next batter is the player whose spot in the lineup follows that of the proper batter who failed to bat in turn, whom you've just called out, and the batting order continues normally from there. If the batter who is now due up is already on base, then simply pass over him and move to the next player in the batting order.

Important: If the improper batter's at-bat results in his being put out, and if the defense then appeals the batting order infraction, that put-out is nullified. The defense gets the out from the batting out of order infraction, but they don't also get the put-out on the play. Taking it one step further, if the improper batter's at-bat results in a double-play, an appeal of the infraction nullifies both of those outs. In short, a defensive manager is wise to know this rule well, since sometimes it's best to just leave well enough alone.

Summary

This all sounds somewhat confusing, but if you learn the rule and approach it systematically you can usually untangle it without too much trouble. Also note that 6.03(b) Approved Ruling includes several example scenarios. These are useful learning tools.

The flow diagram on the right summarizes how to handle each of the batting-out-of-order scenarios:

- Details

- Hits: 136584