Rules

Base Path & Running Lane

Base Path & Running Lane

The first and most important thing to know about the base path is that there is no such thing as a base path (none exists) until a play is made on a runner. The base path is established when a fielder with the ball attempts to tag a runner. Then, and only then, is there a base path. And the base path is a straight line from the runner's position to the base to which he is advancing or retreating.

We're going to talk about that, as well as other important points pertaining to the base path and the running lane:

What is a base path?

The base path is defined in Rule 5.09(b)(1):

"A runner's base path is established when the tag attempt occurs and is a straight line from the runner to the base he is attempting to reach safely."

The wording is important. The base path is established (created) "when the tag attempt occurs." in other words, until there is a tag attempt, there is no base path. And then this: The base runner is out if "running more than three feet away from the baseline to avoid being tagged." At the moment the base path is established (when the tag is attempted), the runner cannot veer more than three feet to the left or right of the base path for the purpose of avoiding a tag.

It's important that a base path only exists when a fielder is attempting to make a tag. At all other times there is no base path (no such thing) and in fact the runner is free (at his peril) to run pretty much anywhere he wishes. There are limits to this (see Rule 5.09(b)(10) regarding "making a travesty of the game"); however, the central point remains: the base runner creates his own base path.

Here's where it gets tricky

It gets tricky in a pickle. When a runner is caught between bases and fielders have the runner in a pickle (a rundown), each time the fielders exchange the ball and the runner reverses direction, the runner has created a new base path . Each time you have this reversal you have a new base path because you have a new fielder attempting to make a tag (and therefore a new "straight line to the base"), and so you have to adjust your view of the base path accordingly. (On a side note, obstruction also comes into play in this scenario.)

So you have to be mindful that, during a pickle, the base path is going to migrate every time there's a throw. Depending on how long the pickle goes on, the base path can migrate quite a bit. When this happens, you invariably get some fan in the stands shouting at you "He's out of the base path!" But you and I know these fans don't know what they're talking about.

What about when the runner actually does run outside the base path to avoid a tag?

Rule 5.09(b)(1) allows a runner up to three feet either way off his base path to avoid a tag. More than that and the runner is out. Of course, you'll never see an umpire with a tape measure, so eyeballing that three-foot allowance takes experience and judgment. One helpful guidelines is noticing whether the fielder attempting to tag the runner, upon making a step and a reach, was able to tag the runner who is trying to pass him.

Abandoning the base path

Well, then, answer me this: If a runner creates his own base path, and if there's no such thing as a base path until a fielder attempts to tag a runner in the base path that he, the runner, has created, then how can a runner possibly abandon what doesn't even exist?

Well, the simple answer is because Rule 5.09(b)(2) says so. In truth, though, it's not really the base path the runner is abandoning (despite the wording in the rule), but rather the effort to continue advancing.

Rule 5.09(b)(2), along with 5.09(b)(2) Comment, tell us that if a runner leaves the base path and in doing so he "obviously" abandons any effort to reach the next base, then you call him out "if the umpire judges the act of the runner to be considered abandoning his efforts to run the bases." The ball remains live, however.

You don't see this very often. The most common scenario is when a base runner mistakenly believes he's been put out and heads for the dugout. There is no set guidance on how far the runner must go before he's technically abandoned the bases; the rule book says that he "progresses a reasonable distance still indicating by his actions that he is out." More often what you see is the runner's teammates screaming at him to get back to the base, or the defense noticing his blunder and putting a tag on. Then it's a matter of who wins the race back to the bag.

One final point. Jaksa/Roder extend their discussion of abandonment by introducing a new concept: "desertion" (Thirteenth edition, p. 48-49). The distinction recognizes that a base runner cannot (technically) be called out for abandonment before he reaches first base. So in cases where the runner can legally advance to first (e.g., on third strike not caught), but fails to, or hesitates overlong, then he is out for "desertion."

Another scenario is when a batter-runner is awarded first base on a walk, but because he is going to be replaced by a pinch runner, rather than advance to first base he goes directly to the dugout (and the pinch runner goes to first). Again, the batter-runner is out for desertion. That said, you might go 30 years without seeing that scenario.

What about the running lane?

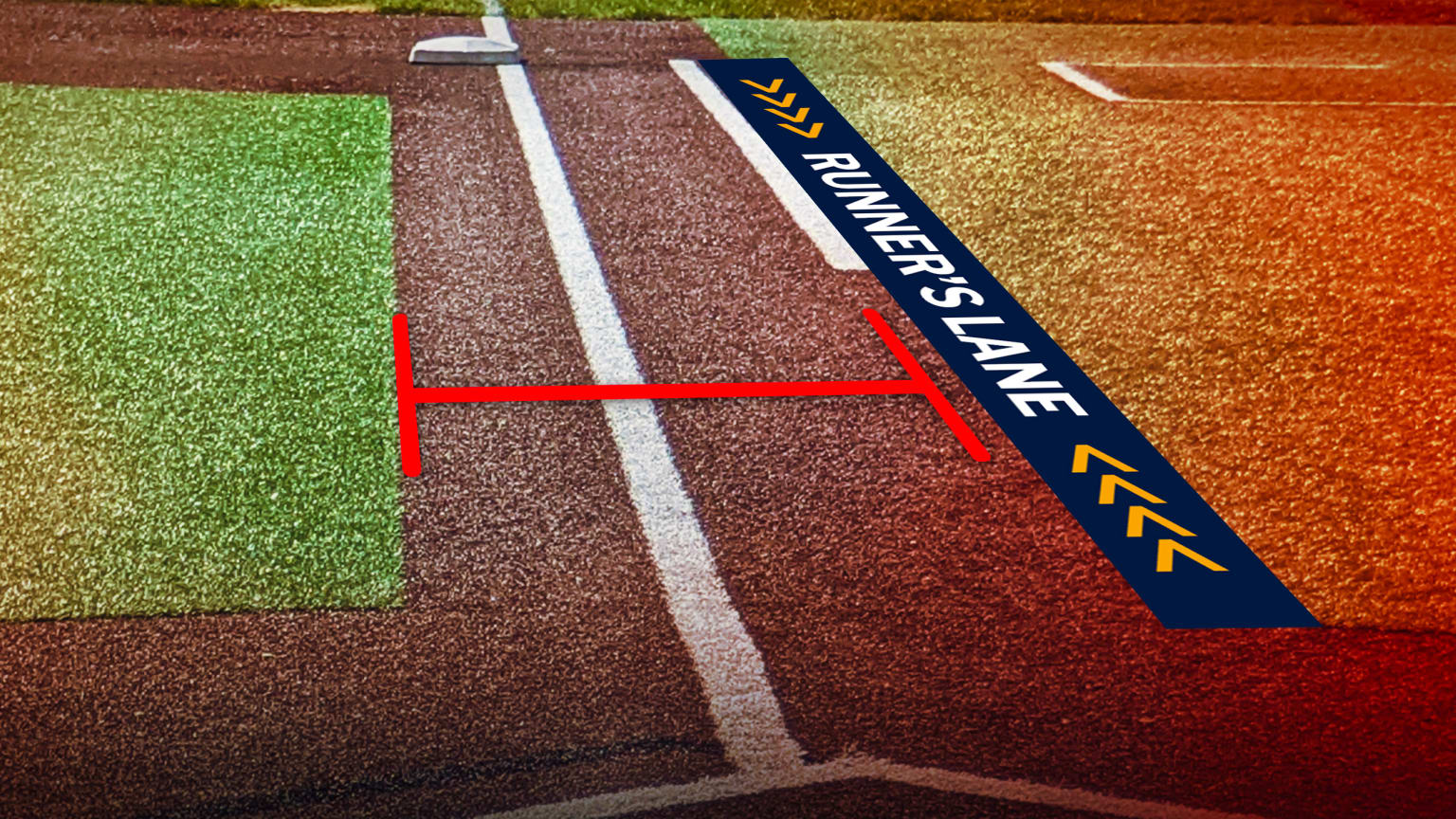

There is a three-foot-wide running lane (54 to 60 inches wide in OBR starting in 2024) the last half (the last 45 feet) between home plate and first base. If you run outside this running lane while a play is being made from the vicinity of home plate (on a bunt, for example), you can be called out for interference. I said you "can" be called out for interference if running outside the lane. But not necessarily. I'll explain.

Existing running lane extending from the first base line to chalk line in foul territory.

New OBR running lane extending from grass line to chalk line in foul territory.

Our rules reference is 5.09(a)(11), which reads in part:

In running the last half of the distance from home base to first base, while the ball is being fielded to first base, he runs outside (to the right of) the three-foot line, or inside (to the left of) the foul line (the grass line in OBR since 2024), and in the umpire's judgment in so doing interferes with the fielder taking the throw at first base .....

When we said that you're not necessarily out for interference when running outside the running lane, we're calling attention to a few wrinkles in the rule. Here are the important points to remember when judging interference on 5.09(a)(11):

- First, let's define the running lane: A three-foot-wide lane (OBR changed this to the wider 54" to 60" running lane in 2024) occupying the last half of the distance to first base. The lines marking the running lane are part of the running lane. That's important.

- When is a runner out of the running lane? The batter-runner is out of the running lane when, during the last half of the distance to first base, one of the runner's feet (or both, for that matter) is entirely outside the running lane at the time that the interference potentially (but again, not necessarily) occurs.

- A throw must be made. If the catcher, for example, comes up with a bunted ball and sets up to throw to first, but then stops and doesn't throw because the runner (in his view) is in the way, you cannot have interference. The fielder must make an attempt to throw to first.

- The throw must be a catchable throw. Using the same example, if the catcher comes up with a bunted ball and then throws wild to first base because (in his view) the runner was in the way, you cannot have interference. The throw must be one that the first baseman has a reasonable chance (with ordinary effort) to catch.

- Note carefully the language of the rule: "… interferes with the fielder taking the throw at first base." So umpire judgment rests on what's happening with the fielder at first base, not the fielder who is making the throw. This is a critical point and is often misunderstood. Points #3 and #4 rest on this point: That if there is interference, the interference is on the fielder receiving the ball at first base, not on the fielder throwing the ball from the vicinity of home plate. You will sometimes get managers arguing running lane interference mistakenly arguing that the fielder who threw the ball was upset by the runner's position outside the running lane. He's entirely mistaken with that line of argument.

- There are two exceptions. There are two exceptions (wrinkles, really) in Rule 5.09(a)(11). First, the runner is permitted to leave the running lane to avoid a fielder attempting to field a batted ball. We know this already from what we've learned thus far about interference – that the fielder has the right of way in fielding a batted ball. Second, noticing that first base itself (the bag) is outside the running lane, the runner is permitted by rule to step out of the running lane for the purpose of touching first base. (This second exception no longer applies where the new OBR 54 to 60 inch wide running lane rule is in effect.)

So all of this rather begs the question: when do you have interference on a running lane violation? Well, the most common scenario is when you have the runner outside the running lane and the fielder's throw to first base is on line, but the throw hits the runner in the back (or head) causing the ball to drop uncaught. This is not the only scenario, of course, but it's probably the most common one. Kill the ball, call the batter-runner out for interference, and return other runners (if any) to their time-of-pitch base.

Rules Variation: High school (NFHS) rules differ on this point. See NHFS rule 8-4-1g. While OBR requires that the throw from the vicinity of home plate be "catchable" in order to have interference, NFHS rules don't make this distinction. Any throw to first base from the vicinity of home plate to retire a runner who is outside the running lane creates legitimate grounds for judging running lane interference.

- Details

- Hits: 287629

Batter's Interference

Batter's Interference

There are three ways a batter can commit batter's interference. He can interfere with the catcher making a throw to retire a runner in the act of stealing a base. Second, he can interfere with a runner who is stealing home. Sometimes these two overlap. Finally, he can commit backswing interference (also called "weak interference"). This happens when the batter swings and, on the follow through, his bat hits the catcher or the catcher's glove. Each of the three case is handled differently, so we'll take them one at a time.

1 - Interfere with a catcher's throw

When a base runner is stealing and the catcher comes up quickly with a throw to attempt to retire the runner, the batter cannot in any way impede the catcher's effort – either intentionally or unintentionally. If he does, then the batter is out, the ball is dead, and all runners must return to their time-of-pitch base.

The most common steal-and-throw scenario is a runner stealing second on a pitch (as opposed to a passed ball or wild pitch). Sometimes you see a steal of third, but not very often. So on a steal of second base, you don't often have interference because the catcher has a clear line of sight to second base.

But sometimes you do – for example, when the batter's swing pulls him off balance and he steps onto or across the plate. If there is a runner stealing second when this happens, you can very easily have batter's interference. When stepping over the plate, the batter can easily bump or otherwise impede that catcher's attempt to throw down to second. That's interference.

Note: If you see batter's interference, but the catcher gets the throw off anyway and succeeds in retiring the runner, then ignore the interference. By Rule 6.03(a)(3), if the catcher retires the runner, then, in effect, the interference never happened. On such a play, then, if other runners were also stealing when the interference is waved off, they get to remain at the base they stole.

We said a moment ago that most of the time the steal is of second base. But not always. Sometimes you get a base runner stealing third, and this is the case where you really need to watch for batter's interference. That's because the throw to third often requires the catcher to throw across the right-handed batter's box. And that's where the batter is standing (if he's right-handed). And you can't expect the batter to simply disappear.

Now, this gets a little bit tricky. There is a common misconception that if a batter remains in the batter's box he cannot be called out for interference. This is not true. The batter's box is not a safe haven. But, as we said, he can't be expected to disappear, either. Add to this that a play on a steal of third happens so friggin' fast that the batter may not even know a play is on until the ball goes whizzing by.

And let's not forget about snap throws down to first base to catch a runner leading off too aggressively, or who may not be paying attention (yep, sometimes they catch runners sleeping). You have the same issue here as you do with throws to third, but instead it's with left-handed batters.

So, with all of this fuzzy grey zone, what's an umpire to do? Well, the wording of 6.03(a)(3) is important here: The batter is out if he "… interferes with the catcher's fielding or throwing by stepping out of the batter's box or making any other movement that hinders the catcher's play at home base." As directives go, you can't get much broader than "any other movement." Batter beware.

The emphasis is important because "any other movement" covers a lot of ground. A lot. So the message is, give the balance of judgment to the catcher. Sometimes a bad throw is just a bad throw and you have nothing. But if the catcher's throw gets disrupted in any way, regardless of intent, you've got to call it.

But again (for the third time), you can't expect the batter to simply disappear. You have to watch and judge for yourself whether the batter made "any other movement" that hindered the catcher in any way. This is a judgment call, of course. Generally (generally), if the batter remains still in the batter's box and makes no movement, then he is protected from interference. If it were me, though, I'd duck. But that's just me.

Here's where it gets even more tricky

The batter's interference play that I believe causes the most arguments is not on a straight-up steal. Instead, it's when the catcher mishandles a pitch (or is handling a wild pitch) with runner on base. The ball is on the ground and runners are in motions and the catcher is diving or grabbing for the ball; at the same time the batter is dancing out of the way while trying to avoid interfering, and in doing so he instead interferes. That's interference. "But I was trying to get out of the way," the batter protests. You're breaking my heart, son. You're out.

2 - Interfere with a play at the plate

When a runner attempts to steal home, the batter has to make an effort to get out of the way of the play at the plate. This can be tricky if the runner is stealing on the pitch, as with a suicide squeeze (which is rare, but it does happen). A play like this happens very quickly and even you, the umpire, probably don't realize what's happening until split seconds before it blows up right in front of you.

More commonly, interference with a play at the plate happens when there is a runner on third (R3) and then there's a passed ball or wild pitch and R3 tries to score. You have the catcher scrambling for the ball, the pitcher running in to cover the plate, and you have R3 barrelling toward home. Get position and watch like a hawk.

You have a similar situation on a sacrifice double-steal. That is, with fewer than two outs and with runners on first and third (R1 and R3), R1 will sacrifice himself on a lame attempt to steal second just to draw a throw so that R3 can then steal home. You don't see this too much at higher levels (16U and above) because the fielders are good enough to defeat the play with fast, accurate throws. But at younger levels you see this all the time. Again, watch this one carefully because frequently the defensive will fake the throw to second but instead hit a cutoff fielder, who then makes a play on R3 at home.

3 - Backswing interference

When a batter swings at a pitch and the momentum of his swing brings the bat around and hits the catcher, or more commonly, the catcher's mitt, this is backswing interference. It's sometimes referred to as "weak interference." When backswing interference happens, you must kill the ball ("Time!") and return runners (if any are in motion) to their time-of-pitch base. However, no one is called out.

Rules Variation: High school (NFHS) rules differ on this point. NHFS rule 7-3-5c penalizes backswing interference (FED uses the term "follow-through interference") when it interferes with a catcher's attempt to retire a base runner. See NHFS rule 7-3-5-Penalty for more information.

- Details

- Hits: 377917

The Tag

The Tag

Tags are such a fundamental part of baseball that it's a wonder there's so much to say. We can talk about catches and tags in the same breath is because both require secure possession of the ball. The definition of a "tag" does not use the term "voluntary release" as does the definition of "catch," but the requirement is the same. I'll explain.

Definition of tag

Here's the key language from Definitions (tag):

TAG is the action of a fielder in touching a base with the body while holding the ball securely and firmly in the hand or glove; or touching a runner with the ball or with the hand or glove holding the ball, while holding the ball securely and firmly in the hand or glove.

Okay, let's break this down:

- For a legitimate tag, the fielder must have the ball held securely in either the hand or the glove. Nowhere else.

- With the ball held securely in hand or glove, the fielder can, in a force situation, touch (tag) a base with any portion of his body, including his gloved hand, foot, non-glove hand, and so forth.

- In a non-force situation, the fielder must tag a runner with the ball held securely in the hand; or, he can tag the runner with the glove in which the ball is held securely. It is not a legal tag if the ball is in the fielder's hand, and the tag is then made with an empty glove.

- Upon making the tag, and in the sequence of events immediately following the tag, the fielder must maintain possession of the ball. If the ball drops or bobbles, this is not "secure possession" and it is not a tag.

The remainder of the language in Definitions (tag) is equally important:

It is not a tag, however, if simultaneously or immediately following his touching a base or touching a runner, the fielder drops the ball. In establishing the validity of the tag, the fielder shall hold the ball long enough to prove that he has complete control of the ball. If the fielder has made a tag and drops the ball while in the act of making a throw following the tag, the tag shall be adjudged to have been made.

This last sentence is where the issue of "voluntary release," while not stated, is implied. If the ball is dropped while making a throw following the tag, this is "voluntary release" and the tag is legitimate.

When is a tag not a tag?

There are cases where what appears to be a tag is not a tag. We've touched on some of these already, but let's be explicit:

- In a force situation, the fielder must have the ball held securely in hand or the glove. He cannot have the ball pinned to his chest, for example, or in his lap, between his legs, or any other way than "securely in hand or glove."

- In a non-force situation, where the fielder must tag either with the ball securely in hand, or with the glove holding the ball securely, the fielder cannot hold the ball in his hand and tag the runner with his glove. This is not a tag.

A few more points about tags

There are a few more points to make about the tag. Some of this is obvious, but let's go over it anyway.

- In a force situation, with a runner advancing to a base to which he is forced, the fielder may tag either the base to which the runner is advancing, or the runner himself [5.09(b)(6)]. In either case, the guidelines we covered in breakdown items #2 and #3 above apply.

- An attempt to tag a runner triggers establishing the base path for the purpose of Rule 5.09(b)(1). The base path comes into existence only when a fielder attempts to tag a runner, and is then a straight line from the runner to the base to which he's advancing or retreating. We have much more to say about this in the article Base Path & Running Lane.

- Details

- Hits: 124622

Infield Fly Rule

Infield Fly Rule

The infield fly rule is pretty simple. The important thing is recognizing when you are in an infield fly situation. When you are, signal your partner to ensure that you're both mentally ready to call it if you see it.

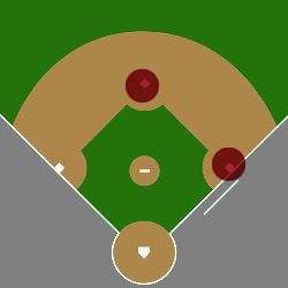

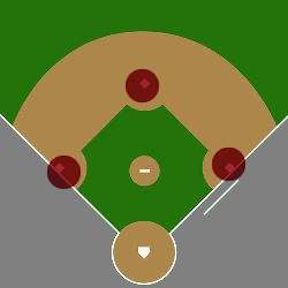

You are in an infield fly situation when these two conditions are met:

- First, you have fewer than two outs.

- Second, you have runners on first and second, or bases loaded, as shown here:

When both of these conditions are met then any high pop-up that "can be caught by an infielder with ordinary effort" invokes the infield fly rule (IFF). The batter is out but the ball remains live, and in all other respects it is simply a fly ball. I emphasized the phrase "with ordinary effort" because ordinary effort means different things at different levels. Ordinary effort for a ten-year-old is much different than for an eighteen-year-old varsity high school player. This factors into your judgment.

The point of the infield fly rule is to protect the offense. It sounds counter-intuitive that calling a batter out is protecting the offense, but in fact the infield fly rule prevents the defense from "accidentally-on-purpose" misplaying the fly ball, then getting an easy double- or triple-play.

The proper mechanic for calling the infield fly is to point straight up with your right arm and calling as loudly as possible "Infield fly! Batter's Out!" If the fly ball is coming down close to one of the foul lines, say instead "Infield fly if fair!" If the ball drops uncaught in foul territory, this is just an ordinary foul ball (the batter is not out), so just wave off the infield fly.

A few important points about the infield fly rule

- The rule says that an infield fly is a ball that "can be caught by an infielder …," but that does not mean that it must be caught by an infielder. Particularly at higher levels, a deep infield fly might be taken by an outfielder coming in. Remember, infield fly is a judgment call.

- An infield fly is not judged by arbitrary markings on the field, such as the infield grass line. You're going to face situations where you call IFF outside the grass line and a coach will scream something like "he's not in the infield!" Ignore him. He doesn't know what he's talking about.

- If the infield fly falls in foul territory (is a foul ball), the rule is waved off and the batter is not out. It's just a foul ball. If caught in foul territory, however, it is simply a caught fly ball – the batter is out, the ball is live, and runners may advance at their peril after tagging up.

- The effect of calling an infield fly is simply this: by calling the batter out, you take the force play off the runners on base. The ball is live, and the runners are free to advance at their peril, either immediately (if the IFF is not caught) or after tagging up (if it is).

- A bunt or attempted bunt can never be an infield fly, no matter how high it pops up. A blooper to the infield is also not an infield fly. How, then, do you recognize an infield fly? Well, my approach is this: If I can look up as the ball rises, then look down quickly to see if a fielder is handling it, and then look up again as the ball reaches its apex, then I have an infield fly. That's a bit fuzzy, I know, but it's the best I can do. A little bit of experience will get you comfortable with calling infield flies.

- At lower (meaning younger) levels of baseball the players (and coaches, too) may not be familiar with the infield fly rule so, when you call it, confusion may ensue and all hell break loose. When this happens your first instinct might be to call "Time" to kill the ball. Don't do it! Instead, let the chaos ensue, but pay close attention to what takes place; call outs on runners tagged off base, if that's what happens, and when all action has stopped you can handle the inevitable argument. Your response to the argument is twofold: First, explain the infield fly rule. Second, explain that players and coaches, not umpires, are responsible for maintaining situational awareness.

- Details

- Hits: 75920